I can say from experience that he doesn't work much as a publisher. He works his psyops machine throughout the day, here using a light touch, here pulling that lever with a manic hostile force. He also has time to set up false hold music for the employment department calls, and shunts my Author Central phone calls to criminal scammers. He has time to hack my publisher and delete other submissions.

The overall profile presented in this post is of someone who hacks hard and does it a lot. Since I know he uses AI to create social media avatars, I suspect he relies on AI to read incoming manuscripts.

At this stage of his career, Greg is employed as a full-time criminal. Almost every day I feel his rage. But these emotions were evident when he ran Image, too, when he hacked me with child porn and seized on my then-wife's phone to get his peeks. Therefore Greg has been possessed with this great sexual rage and need to cause harm for a long time.

His child targeting and child death hacks are the most disturbing to me, naturally. Something happened to Greg to make him do these things. I have speculated that he was molested as a child. A person doesn't simply emerge into the world with a desire to target kids . . .

It makes sense that he sends dick pics to women, as he did to my date, and torments women like Camilla at Eugene Weekly. When she signed up to investigate Greg, I never heard from her again. But I did hear from someone in her office who told me their voicemail had been mysteriously replaced. I'm sure he hacked Camilla every which way, until she wept and Greg smiled at the pleasure of her suffering.

I believe Greg's predator behaviors with respect to women serve as an enjoyable activity in the absence of sex. He's isolated and sexless, enraged by rejection and the circumstance of age, and he's getting back.

He doesn't only hack women. But the adolescent porn he spoofed to me supported the sex trafficking of girls and financed the killers who made the film.

Greg is a Russian-style porn hacker. When he goes to the Dark Webs for more techniques, he's learning from men who traffic girls. Even when Greg hacks men, he's a misogynist. One time he loaded the top of my Facebook followers with Russian soldiers, prostitutes, and a child porn operation. Greg likes to keep it scary. Guys who cut women on gurneys and sell toddlers on the black market are "strong men." They assist Greg in his campaign of terror. He uses this material because he wants you to shut the hell up, now. He wants to show that he's the one in charge . . .

October 20, 2025 . . .

Last week I called the unemployment department for the fourth time over three months. My online access had been inexplicably blocked. Each time I called I was able to type in a claim on my phone, and each time the call went to false hold music. I used to work at OED, so I know what hold music they used. I looked it up and found they haven't changed their hold music.

Each time I was on the phone for hours. No one ever picked up. Even during Covid--the highest call volume in history--I could talk to an agent eventually.

Last week I hung up, after waiting too long, and an OED employee called and said she saw I had tried to file a claim. We filled out a claim together on the phone, and I discovered I do have a valid claim. There are still a few steps to complete. She recommended I work with Worksource to finish everything up.

Someone at Worksource confirmed that OED uses the same old hold music. Greg used generic classical and wind instruments to create fake hold music and kill my claim. ("Fake OED Music," August 16).

Greg has set up fake voicemails at Eugene Weekly and even at my doctor's office ("Continues Email-Deletion Campaign," January 25).

Meddling with employment insurance is considered fraud or theft, a possible felony in some states. Maybe presenting my case to an Oregon senator would go somewhere.

But since Greg didn't "log in" or leave an IP, he won't get caught--at least not until someone knowledgeable and competent can review these pages and examine my computer.

Greg continues to use his psyops of rhythmic hissing on my computer ("Psychotic Harassment," July 26). But I try to cover it up with white noise or music.

I looked up the phone number that showed as "Salem" on my phone, and found it's linked to a PI number when I Googled it. But PIs don't pretend to be government employees if they want to keep their license.

This is how OED hold music actually sounds:

I hope that some of you could print out these files and mail them to the Seattle FBI. It seems the only way to supply them with the complete file.

Greg has hacked with child death images, interfered with unemployment services, killed jobs, and used a psyops technique to cause grievous harm. I believe these are crimes that the FBI would notice if they were able to see them.

[Note: 4/27/25]. This screenshot has recently been blurred by Greg the censor (and the original email deleted) because it shows that the editor invited me to submit. She says, "Please send me any of your writing you'd like me to consider for hobart." She also says she'd love to hear what I've done with my writing since graduating from Iowa.

Spoofs My Landlord and Tries to Get Me Kicked out of My HouseOn January17 2024 I received a spam letter that stated my Facebook account was going to close. I took a screenshot of it. The next day I saw that the letter had been texted to my landlord from my phone, known as spoofing. But I hadn't texted her this.

When I tried to explain spoofing to her, she didn't understand it. She said, "This was obviously sent by you. I can see your email in the screenshot." Of course my folders are in the picture. I was the one who took the screenshot.

I tried to explain that a hacker has total control of your phone. He controls all your photos and screenshots, and all the functions. If you take a nude selfie, for instance, your hacker can send it to your husband's best friend, from your phone, so that it appears that you sent the pic. One purpose of spoofing is for a hacker to send disturbing images etc. to your boss, your spouse, your kid--to cause rancor and distrust in relationships, because such texts appear to come from your phone, your name. But it's just a spoof, a trick. Your hacker is the one who sent it.

My hacker wanted my landlord to believe that I'm the type of person who sends spammy, creepy, and threatening letters of this kind.

from Law Enforcement Tips the ScaleJune 24, 2025. I had a terrific conversation with the Eastern University HR manager last month. When Greg announced that he was teaching there this summer--and exclaimed how happy he was--I called HR. Greg has shot down several of my applications to teach at universities, as I have discussed. But more than that, I wanted to let her know that Greg sends child porn and all the rest of it. People like Greg should be challenged.

HR's biggest concern was that Eugene law enforcement had found alarming items in this GW file. She said it wouldn't be legal to fire Gregory Wolfe without having been convicted first. But she agreed it was a brand issue for the college, and my city's law enforcement action gave credibility to my allegations. She said she was going to look at these pages and have some "meaningful conversations." . . .

Another Editor HackedIn October 2023 I was going to submit a story to my friend who runs a literary journal in Serbia. She had asked me to send a story, and seemed disappointed when I had told her I couldn't separate a story from my published book. Then I found two stories for her. In the exchange below, she reveals that she was being hacked.

November 1, 2025. Greg attacks my class again, dropping calls and making static on the line. Greg loves this kind of harassment. He can use his hacking tools and try to sour professional relationships.

Interaction with Eugene Weekly Editor

December 26, 2024. I ran into Camilla, the editor of Eugene Weekly the other day, out front of the magazine's office--the one who volunteered to do an article about Gregory Wolfe's hacking months earlier but went silent. I believe she went silent because she was hacked. She was about to go into the office when I was stopping by to tell her the news about the police referral to the FBI. She seemed quite spooked. She put on a mask and didn't want to make eye contact. When I asked if she'd been hacked, she said, "Nope."

Greg Places His Face on My Blog as Warning

March 20, 2024. Greg placed his face on my blog after I posted "A Christian Leader's Life." My blog has always used the picture on the top post for the site picture (after two or three days), no matter how popular a post below it might be. This Moses pic was on my blog for two weeks.

The Censorship Publisher

January 6, 2025. I got an email from a publisher this morning telling me that an old manuscript I submitted to her years ago had been rejected without their knowledge, due to a "possible bug." I think that bug was named Gregory Wolfe.

Spoofs Dick Pics to my Date

December, 2022. I met a Latina who managed a bowling alley at Valley River Center. We planned to go out on a date.

The screenshots were deleted from my phone. It's lucky that I had posted them in a private Facebook post.

He also placed a file called "Spoofy Files" that shows a thousand hacks Greg has done, not worth showing as most of them come from this post.

Publisher Lawrence Knorr accepted "The Lord's Hacker" in September 2024. A couple of months later, he told me on the phone that the Christian leader's character was interesting. I asked him if the hacking moments seemed too fantastic, and he told me he believed they could be done.

Five months after that, he released me from my contract. He said that I had complained too much about my editor's rewriting my characters and the staff had lost their generosity toward me. They insisted they were only trying to "help" my book.

He obviously arrived at an about face, and I believe he had Greg's help in that. Also, a publisher writing a negative review about a character in an email that promised a termination letter, seven months after the book's acceptance, seems unaccountably strange--especially since the publisher had read the book before and claimed to like that character . . .

The presentation suggests that the closure was due to Greg's absence. Of course, Greg wanted to give that impression. And there is an obvious intention to communicate that it's still closed! You have to select an ambiguous link at the bottom ("details of closure") to see that the journal is now open.

[I had to click on "Details of closure" to see that Image "did not close." This information was not on the main page.]

I wanted to address any who might believe I have no evidence, simply because I lack an IP or a photograph of my hacker caught in the act. As Judge Charles Carlson told me at the hearing, I have evidence that would be persuasive in civil court, and my assertions raise many questions that point directly to Gregory Wolfe. (Carlson said this in 2022, when I had less evidence).

For instance, who wrote the fake Image search results for Gemini? It had to be someone who is a master hacker and who hates Image. I doubt there are two people who fit this description. It was Greg.

Who placed Greg's picture on my blog for two weeks, a threatening gesture, after my post went live? Only my hacker would place his image on my blog.

Who removed the many followers of this blog right before I posted the Gregory Wolfe post? Some other nemesis?

Who deleted the photo I took of my son sitting in front of his computer?

If it was a different hacker, he must have been very sympathetic to Gregory Wolfe and spent a lot of time covering for him and concealing his crimes.

_________________________________________

(after 5, the post continues 1 through 4)

At any rate, 80,000 isn't a high number these days. It's Greg's number. But he's even working to keep his own low number from reaching 80,000.

Publisher Lawrence Knorr accepted "The Lord's Hacker" in September 2024. A couple of months later, he told me on the phone that the Christian leader's character was interesting. I asked him if the hacking moments seemed too fantastic, and he told me he believed they could be done.

Five months after that, he released me from my contract. He said that I had complained too much about my editor's rewriting my characters and the staff had lost their generosity toward me. They insisted they were only trying to "help" my book.

He obviously arrived at an about face, and I believe he had Greg's help in that. Also, a publisher writing a negative review about a character in an email that promised a termination letter, seven months after the book's acceptance, seems unaccountably strange--especially since the publisher had read the book before and claimed to like that character.

I believe Greg hacked Lawrence, just as he has hacked so many other publishers, and so the latter was forced to adjust his feelings and attitudes about that character. He must've figured Greg was reviewing our emails, and he wanted Greg to leave him alone.

The one commonality hacked people share is that they say very strange things in their rubber-legged, shaky-fingered panic.

It's true that text can go wonky on its own sometimes, but Greg's italics are always meaningful. In the italics above, I believe Greg is disputing that my book will ever be published in book form.

It shows that Greg is a censor and he has a lot to hide. This is how he spends his life, hiding things about himself. Block, block, block!

It's a subtle difference, but Greg's changes to screenshots are always subtle. There's a big difference between clicking on a profile pic and seeing it in full view. Greg intended to present an image of a military man with a delicious bloodlust, and this man filled my screen when I saw him.

His dream of having 4000 Hegseth Christian friends to follow and praise him must be dashed. He clearly blames me for all his troubles.

I have researched this, and Workday is supposed to be available even when you don't have an active job. This is what the homepage is supposed to look like, below. My home page used to look like this before it was changed to operate at 20 percent.

Greg is posting photos of himself that suggest a broken and sensitive soul on the edge of tears. It made him suffer that his targeting of kids and other crimes were brought to light.

When I checked the "followers" option in settings yesterday, I saw it was back, and I restored it, though he may disable it again. But I still have only the one follower. I don't expect anyone who knows about me and Gregory Wolfe to follow my blog though.

Greg is using the "Huh, what?" strategy regarding my assertions. He didn't delete my followers. He didn't disable comments. He didn't take this post offline. What motivation would Greg possibly have to manipulate this blog about him?

I can guarantee that the young hotties Greg invites to hotel rendezvous don't care what he did so long ago. But some of them might admire him if he told the truth about who he is and apologized.

We showed the Christian world what he's about, but he's moving on.

I don't receive notices from Quillette. It's true that the hacked think almost everything is a hack, so it could be this email is a coincidence. But Greg likes to communicate with emails and memes, because we have an intense relationship and don't talk. When I was writing my book two years ago, my inbox was jammed with lawyer ads about defamation etc. It was obviously Greg generating those.

"In the wee hours of the morning of January 27, 2013, a Wikipedia editor named “Qworty” made a series of 14 separate edits to the Wikipedia page for the late writer Barry Hannah, a well-regarded Southern author with a taste for the Gothic and absurd.

"Qworty cut paragraphs that included quotes from Hannah’s work. He removed 20 links to interviews, obituaries and reminiscences concerning Hannah. He cut out a list of literary prizes Hannah had won.

"Two edits stand out. Qworty excised the phrase 'and was regarded as a good mentor' from a sentence that started: 'Hannah taught creative writing for 28 years at the University of Mississippi, where he was director of its M.F.A. program …' And he changed the cause of Hannah’s death from 'natural causes' to 'alcoholism.' But Hannah’s obituaries stated that he had died of a heart attack and been clean and sober for years before his death, while his role as a mentor was testified to in numerous memorials. (Another editor later removed the alcoholism edit.)

"The answer to this question is on the one hand simple, almost trivial: Qworty turned out to be another author who had a long history of resenting Hannah. The late night Wikipedia edits are certainly not the first time that a writer’s ego has led to mischief . . .

What was especially charming about this hacking trick was

that my post explores Greg’s manipulation of my posts, stories, novels, and

essays. I returned to the main-page post yet again and highlighted a phrase

that I had written in the third draft and screenshotted it. Only then was I

able to copy the final draft into my GW page.

It shows that Greg doesn’t care about committing censorship, though he has posted about his high morals regarding the subject on his site before. It might also suggest that he thinks he’s once again at the end of his rope, and so angry he doesn’t care about appearances. We know he’s been there before, when he lost his audience earlier this year.

November 21, 2025. I got very lucky when EPD manager, officer Kelsey Anderson forwarded my case to the FBI, even though the FBI doesn't pursue most hacking cases and may not tackle this one. Anderson's nod gave credibility to a case that's difficult to talk about to most people. Though I've been able to convince one cop, one judge, and one attorney that my case has merit, most of them refuse even to listen. Older people, especially, can't believe that a top-drawer hacker can hop around to public and private computer systems at will. It's not the world they're used to. In addition, you would need a Mark Zuckerberg to catch Gregory Wolfe, and most cops have only community-college-level experience in IT. That's why I took it upon myself to get the word out.

Judges and Law Enforcement

They do everything by the manual. The FBI even has a specific technique of taking phone calls. They pepper the caller with snarky questions and comments. "What's this guy's motivation?" or "I can guarantee he doesn't have any interest in your Facebook page." Then he or she begins the rapid closure of the phone call, talking in the dazzling speed of an auctioneer: "Thank you for calling the FBI. This call will be documented and you are free to follow up with a complaint." And they hang up on you. All intake people do this exactly the same way.

I know they are looking for words like "I'm going to kill you," etc. and that they are trained to dismiss anything about social media or otherwise frivolous concerns. But my hacker, in fact, uses social media and my Google page as a template in which to present child death images, underage porn, a photo of my friend who committed suicide, etc. It's true the FBI is looking for extortion and bodily harm, but my harassment case is horrifying and dangerous, not frivolous, not imagined, not paranoid, and deserves an investigation.

Judges also tend to dismiss almost all hacking claims. I've stood before a few judges who were visibly angry that I even brought a hacking case. Even while newspapers and attorneys say that Russian-style hacking is increasingly common in America, judges and law enforcement respond to this reality by refusing to believe it even exists.

Since this response makes no logical sense, I believe this shutting of the eyes is a psychological reaction. After all, law enforcement has not kept apace with the high-tech criminal hackers. To open up law dockets to hacking cases would be like opening a portal to a howling infinite that would cause headaches for courts, judges, and law enforcement.

And this is why judges and law enforcement regard with anger and distaste the person who brings forward a hacking case. They can't do anything about it! They don't have the tech. Psychologically they have hardened themselves against you, knowing that your possibly reasonable case can't even be considered. You almost become a criminal in their eyes.

The other day I sent a new picture of my son to the Christian scholars. He's ten, wears a hat over his long hair, and has a natural, happy smile. Even the most hardened prisoners know that children are sacred. But Greg, a "Christian," doesn't know that.

November 6, 2025. It was amazing that EPD's officer Kelsey Anderson forwarded this case to the Seattle FBI. But since Greg "edits" digital law enforcement files by removing the content that pertains to my son, I don't believe they ever received my complete file. When I have contacted the FBI, they don't seem to have the complete file. But they are trained to avoid direct questions and to get off the phone fast.

I hope that a few of you could print out these files and mail them to the Seattle FBI. Not to sign anyone up for chores, but if anyone has the time and wants to help me and my son, this would be an effective measure against Greg's deception. The FBI has an online data collection method for hacking cases, and Greg has a habit of selectively deleting evidence from digital files.

I also believe Greg can reroute my mail into a ditch. They use a digital system now and Greg has made many changes to my postal addresses, one resulting in a fraud alert being placed on my account. I fixed it, but it took some doing.

Greg has hacked with child death images, interfered with unemployment services, killed jobs, and used a psyops technique to cause grievous harm. I believe these are crimes that the FBI would notice if they were able to see them.

The thing that always saves me is writing. I found my way into a draft of a short story this morning. It finally came together and I loved working on it. That's the thing that always kills Greg's psychotic poison.

I mentioned this next story in The Lord's Hacker. When my wife and I split up and I moved to Cincinnati, Greg seized on the weakness of the moment, hacking me especially hard after I had lost my family. He was hacking me constantly and interrupting video calls with my son and draining my phone battery, and a lot more.

It was the first time I realized that Greg was trying to break me down. His hacking succeeded in making me want to swim in the river and not return to shore. He took my pain and tripled it. It's an attractive technique for a hacker because you can't take a screenshot of it, or document it in a clear way. But I understood that Greg had an evil in him that was larger than anything I had experienced.

Then I called a suicide hotline number. Greg keeps track of my calls and listens to them as well. After that night, he left me completely alone. I was able to write without my computer updating for one hour, and there was no other interference. The story I was working on was going very well, and I found a romance to my writing life in Cincinnati. After two weeks, I posted, "Feeling Byronic." That meant I had taken a gloomy mood and found something good in it.

When Greg saw that post and knew I wouldn't commit suicide, he gave me one of the worst hackings ever. It didn't bother me. I had come out of the bad place. But I'm certain he was enraged because I was still alive. He had many beautiful daydreams about my death, and I took those dreams from him.

I think of Jane as his partner in crime now. Like so many weak people, she tried to be a badass hacker. I discuss that in "Jane Smith is Breaking the Law." She had once been the lightest, most joyful, lovely person. Yes, she had been in the cult Christian Israel, but she was something special. Then in middle age she was so broken and embittered--after caring for five kids alone--that she started to rely on Greg for his murder techniques. She has always relied on strong men.

But she didn't understand that Greg is weak too. He has a surface persona that isn't really him, and this surface conceals a great need to inflict harm. People who have a great need to inflict pain are weak, even if they are killers. They have a small flame. They aren't substantial. Their surface qualities are borrowed and faked. They hide a black essence with a smile. They know they're not human in the best sense. Their violence comes from weakness.

I can only speculate about the source of Greg's rage, but I have wondered if he was molested as a child. This would explain his targeting of children that I have seen, his use of child material in his porn hacks, and other things involving kids that I haven't seen but are surely there. Almost always, child molesters and those who target children were molested themselves. Whatever happened to Greg, it was something very bad. I have no sympathy for that by the way. I believe the best way to handle a child molester is to-- I'll leave that sentence unfinished.

When I dated Jane, she was often visiting men in prison. She visited Mr. Christine who had kidnapped his kids from child welfare workers at gunpoint. And she visited some other guy who was in prison. She showed me his Facebook profile. He had wrapped clear tape around his face so that he looked like a bad facelift and deranged. She has always had a thing for "strong" men. To her that means men who are capable of violence that can be used to help her.

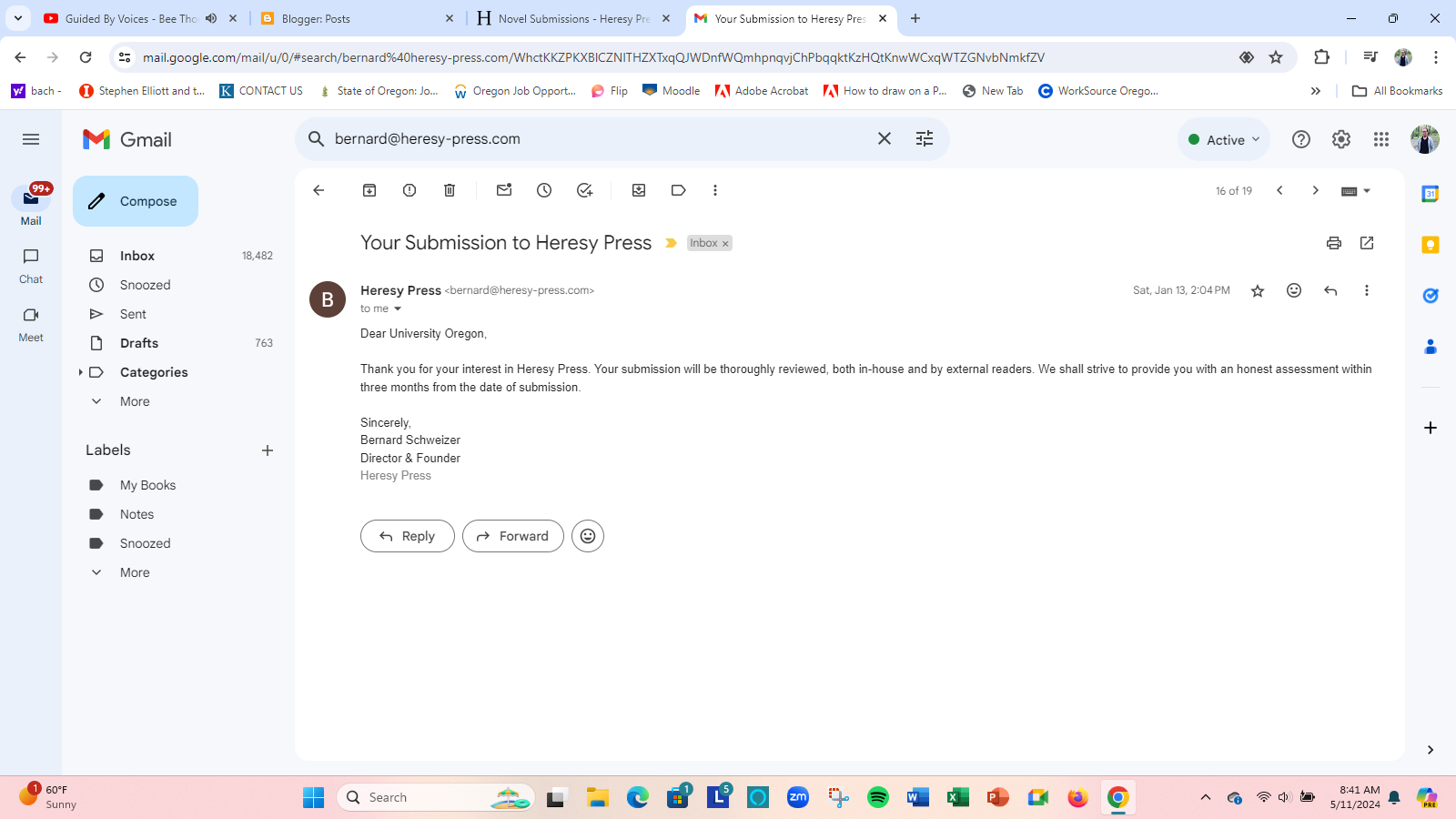

In 2023 Bernard Schweizer, editor of Heresy Press, invited me to submit a book. We hit it off, agreed on a lot of things, and sent occasional friendly emails. Then I made the mistake of telling him I had a hacker, since I figured he'd get hacked anyway if he accepted my book. I thought he might bristle at the censorship and stand up to it. Part of his mission involves standing up for free speech. But he went gloomy and wasn't interested anymore. This is a different case, since I was the one who mentioned it, but I figured telling him directly was my only chance. I don't know if he was hacked.

In 2023 Lara Dodds, English chair at Mississippi State, was warm and friendly in our phone conversation. She believed she could find some online classes for me. During our next conversation, the following month, she was distant and rude. She had no classes--a complete switch in tone--and there was no invitation to apply again. Such things happen, but when they are always happening, it feels very suspicious. It was the severe change in tone that was telling. I know that class availability can change in a department.

Margaret Perrow, English department chair at Southern Oregon University, emailed in 2022 that she was sure she could find a couple of classes for me. She complemented my resume and wrote back a hasty sorry, no jobs, and she would be in meetings for a month etc., adios forever. She seemed to have the panic that hacked people tend to have.

In 2022, the assistant of publisher Dennis Stovall, at Ooligan Press, invited a manuscript because I was friends with one of their authors. Then I received a rejection without comment. Since she invited the manuscript, I counted the lack of a single greeting in the rejection to be highly unusual and a likely hack. Publishers write back when rejecting a book that they invited, at least to say it's not a good fit, best of luck. Hacked people know they can't be in communication with me at all.

In 2022 an English chair in Ohio whose name I can't locate, because we only spoke on the phone, told me my experience sounded amazing. She looked at my site. She said they had ten positions opening up the next term, and advised me to apply immediately. When I applied and hit submit, there was no "success" note. The application simply disappeared--a common story because Greg deletes many of my applications. I called the chair and spoke to her secretary, who told me that none of those ten jobs were open. They had all been filled since the previous day.

Again, I understand the terror of a hack. I've felt it myself. But it's time to understand that hacking is a form of censorship--or a criminal nudge in a hiring decision--and remaining still and silent amounts to working hand in hand with a censor and a criminal. It's impossible to bemoan censorship in one case and capitulate to it in another. Things might change the more we learn about the Dark Web world of Russian-style porn hackers.

He also placed a file called "Spoofy Files" that shows a thousand hacks Greg has done, not worth showing as most of them come from this post.

June 15, 2024. Greg rewrote this email that I wrote to my friend Jose. I took his creative writing class for fun. You can only see the difference when you look at "Ryan Blacketter wrote," right below his response, at the bottom. Greg rewrote my initial email. He receives the emails I send to others, reviews them, deletes them, or rewrites them, before sending them to the intended recipient. He also receives emails that others send to me, and he doctors those, deletes them, or sends them to me. This is part of his censorship strategy.

It's rare that I can actually see his doctoring. But this shows it. In addition, Greg seems especially to use my Hispanic and Black friends for his hacking fun. Compare my email, at the top, to the rewrite under "Ryan Blacketter wrote" at the bottom.

If I believed our FB interactions amounted to much--enough to bump her into my FB profile list--then I would have said so. If I was trying to hide our very few FB interactions, I wouldn't have presented them to public scrutiny. Instead, I would have made those pages private, like a sneak. Any speculation about what I was thinking is, of course, mindreading.

Also Drew is featured. Drew wrote a recent review of Horses, and Greg has pretended to be him in texts he has written me. I suspect Drew was hacked. ("Greg's Spoofs," 9/12/25). You can see in the screenshot that my recent post about Drew's podcast was restricted.

My son, in the middle, is also featured, though we have had almost no contact on Facebook. I didn't name him or tag him when I posted his photos. Since Greg enjoys subtle meaning in his threats, I suspect it's meaningful that my son is right in the middle.

My student Anand is also on this profile list. Greg has dropped our calls many times during several classes, ever since I mentioned Greg during a class six weeks ago (yes, Greg was listening).

Mary Owen is here too, daughter of Donna Reed. Greg hacked Mary two years ago when she was finishing a blurb for my book. I had a draft from her and completed it myself. But I've had almost no contact from her since, except for occasional FB contact recently, though she and I were close friends.

July 26, 2025. Greg has been making my computer hiss again. It's hard to talk about this because it sounds crazy. I repeat the telling of this since it's ongoing. Also, my previous post about this issue has been deleted.

Criminals use these dark webs techniques more than we know, and Greg is more of a criminal than we might know.

I mentioned the woman, a friend of a friend, who claimed that someone had planted a microscopic radio in her nasal cavity [Post deleted. Greg might restore it, but I can't find it now]. From a remote distance, this psychopath could fill her head with shrieks and sounds by moving his joy stick. Who's going to believe that? Nobody. She's obviously crazy! But the FBI believed her and worked to find the villain who did this to her.

Greg is also very high-tech and interested in achieving similar torments. When I was writing "The Lord's Hacker"--a book he didn't want me to write--he repeatedly employed a rhythmic hissing at a certain pitch, and it affected my inner ear. Then he finished it off with a volley of hacking techniques that wore me out and reduced me to an incoherent state and I went to the hospital for five days.

It was an impressive hack, with a rising arc, a climax, and a skillful denouement, almost as if he were laying me out for the night or beyond--in a long box, perhaps.

Greg seems to save the hissing for when he's really angry, such as when I introduced new email addresses to my shoutout page the other day.

He uses this psyops method because it does physical and psychological damage. I've captured the sound on a video recording and posted it in another entry here, but it's hard to experience it through the recording. After all, computers do hiss sometimes. It's normal.

But when my computer awakens to sustained and rhythmic hissing, at times when Greg would be especially angry--like when I was writing a book about him--I witness a meaningful pattern. It's not a normal computer sound. Also, this psyops seems of a piece with his other death-dealing hacks presented here. He's surely one of the evil characters who hunts the skies in the dark webs.

Submissions, Round Two

September 22, 2025. My second round of submitting "The Lord's Hacker" is already fraught with evidence of censorship. My search results for small presses one day were extremely limited, because Greg controlled the search. Only two lists were available, and they contained information from ten or fifteen years ago. I posted about that.

When I sent an emailed submission to Clash Books the other day, I received no automated note in return, nor when I wrote them on their form. Every time I've submitted without receiving an automated note, I have received nothing back, no note, no rejection. It goes out to the wind. Greg has deleted countless emails. It's possible some presses don't use automated notes, but the fact that I don't receive rejections suggests interference.

When I submitted to Autumn House Press on the same day, I discovered that the bottom of the page was fake, and I was submitting to a vanity press. I'm sometimes hesitant to mention such things because it sounds so fantastic. But many of Greg's hacks show an impressive ability to merge pages or create a false bottom of a page.

I've posted about this censorship, but I'd like to place these and future submission hacks on my featured posts, in one ongoing entry. Greg's censorship is one of his greatest moral failings, especially since he calls himself a "renowned" literary editor and publisher. He might compartmentalize his crimes and pretend they don't exist, but that's his fantasy, not ours. This might be his last chance to salvage his reputation and do what's right. But I don't believe he'll change. It seems the only way he knows how to fix things is by hacking. But that activity is precisely what will sink his reputation and his legacy.

Greg removed two lists of publishers from my desktop. They were both current lists of houses that accept submissions without agents.

Soho Press is listed as a publisher who accepts unagented books, but they also stopped doing that years ago.

When I returned to Autumn House, I saw they aren't in fact accepting submissions! I have seen Greg pull off this move before. He slows down or freezes the screen while he creates a false part of a website or writes a false note--whatever he wants to do. As I have said, he's very high tech, and quite elaborate.

The presentation suggests that the closure was due to Greg's absence. Of course, Greg wanted to give that impression. And there is an obvious intention to communicate that it's still closed! You have to select an ambiguous link at the bottom ("details of closure") to see that the journal is now open.

[I had to click on "Details of closure" to see that Image "did not close." This information was not on the main page.]

Publisher Lawrence Knorr accepted "The Lord's Hacker" in September 2024. A couple of months later, he told me on the phone that the Christian leader's character was interesting. I asked him if the hacking moments seemed too fantastic, and he told me he believed they could be done.

Five months after that, he released me from my contract. He said that I had complained too much about my editor's rewriting my characters and the staff had lost their generosity toward me. They insisted they were only trying to "help" my book.

He obviously arrived at an about face, and I believe he had Greg's help in that. Also, a publisher writing a negative review about a character in an email that promised a termination letter, seven months after the book's acceptance, seems unaccountably strange--especially since the publisher had read the book before and claimed to like that character.

I believe Greg hacked Lawrence, just as he has hacked so many other publishers, and so the latter was forced to adjust his feelings and attitudes about that character. He must've figured Greg was reviewing our emails, and he wanted Greg to leave him alone.

The one commonality hacked people share is that they say very strange things in their rubber-legged, shaky-fingered panic.

He had the motive to delete all of my blog followers, disable comment functions, delete some of my posts that focused on Greg targeting my child, delete my emails about Greg, delete emails his friends sent me, delete emails that had attachments of screenshots of his work. He had the motive to delete police reports I’ve filed about him, delete records before I requested a restraining order, delete my emails to Oregon Judicial Watch. And he had the motive to cripple my Amazon author page right after Lawrence Knorr at Sunbury Press accepted The Lord's Hacker (a book about Gregory Wolfe). When that wasn't good enough, he hacked Knorr, resulting in a dismissal of my contract, and on and on ("Greg Hacks Another Publisher"). And these are only the hacking incidents in which Greg was saving his own butt!

Criminals say that if you want to kill someone you should kill some random person you don’t know. Then the clues won’t point at you. That’s true for choosing your hacking victim as well.

Last night I started watching "The Wolf of God," when I discovered the subtitles were off. When I tried to turn them on, the screen froze, then I was kicked out. I tried again and was thrown out. Then I discovered the subtitles were on, but the screen was black. (Two screenshots below). It was definitely a Gregory Wolfe operation.

Like some of the very bad characters I mentioned above, Gregory Wolfe has a surface belief in the church. He has devoted a lot of time to writing about his faith, but he compartmentalizes his evil behaviors, justifies them as holy acts in defense of the church, and probably even forgets about them sometimes. He wants to believe that he's a true son, and so he works fast to disable or hush up any negatives about the one true faith. In this way, he proves to himself that he really is working on the side of the church. I doubt he has any trouble justifying the illegal porn, child targeting, and all the rest of it.

It's also strange that he'd believe that covering up evil in the church is somehow working on the side of the church. Since that makes no sense, I think he simply decides to believe it, while forgetting that the evil people are in fact enemies of the church, and that he's one of them.

This photo presents a smiling and successful Gregory Wolfe, editor of Image Journal. He's got the Christianity Today vibe. He looks warm here, and probably wants to fit in with normal Christian culture to make his brand attractive. I know he had narcissistic personality disorder then, but at this time his illness remained hidden.

In 2022, only one of the study guides showed the midterm essay prompt, but most of it was bot language, beeps and bops, with my name or the name of the short story appearing. Then it turned into a student business essay at the bottom of the page.

June 24, 2025. I had a terrific conversation with the Eastern University HR manager last month. When Greg announced that he was teaching there this summer--and exclaimed how happy he was--I called HR. Greg has shot down several of my applications to teach at universities, as I have discussed. But more than that, I wanted to let her know that Greg sends child porn and all the rest of it. People like Greg should be challenged.

This is how OED hold music actually sounds:

August 13, 2025. Determining the accuracy of a hack isn't an exact science. Sometimes I know what happened right away, and I continue to know what happened. Other times I decide a post is weak or it doesn't illustrate what I had thought, and I cut it.

Regarding Sunbury Press, at first I believed I was simply let go from my contract, and I didn't think about it for a couple of months. Then, out of the blue, several facts presented themselves to make me certain that Greg had hacked the publisher. Your mind can work on an issue while you're not thinking about it, of course. Those posts that take a little time are often the most illustrative.

In other posts, I simply believe Gregory Wolfe did it. He has a history of sending me porn, for instance, and I know that he has sent other people porn. In 2018 I found a fake Gregory Wolfe Facebook account that had a banner full of penises. I discuss this elsewhere. Whoever made that account knew about Gregory Wolfe's dick pics. I came to know about them personally five years later when he spoofed pics to my date via my phone.

That might not add up in criminal court every time, without an IP. But as Judge Charles Carlson told me, it could add up in civil court, where a "preponderance of the evidence" test is used. That's the test I do my best to follow here. I'm not a lawyer, but I try to present the reasonableness of my assertions in my own layman's way.

When this post first went online, Greg's face appeared on my blog in warning. All my blog followers were deleted. Comments were disabled. And the post went offline. Only Greg had the motivation to control this post about him, and he executed the attack on multiple levels, within two or three days. The connections are obvious and persuasive, despite the lack of an IP. This satisfies the preponderance of the evidence test.

In other cases, patterns are revealed. Greg has sent many death images and many pictures of my son. Since I know he likes to create terror with illegal porn, I extrapolate the same motivation when I receive child death images and other death images of old friends who are actually dead. I know I don't have two hackers, one for porn and one for child death. It's Greg doing both of those.

It's fascinating that Greg doubles down on his hacking when he's been exposed. I believe he started hacking as a way to scare his enemies and protect his brand, but now his motivation has devolved into pure ego. He's like an insane, dying general lying in the desert outside of a village, shooting at anything that moves--women going to the well, children playing soccer, his own men. There's no point to it anymore. He just wants blood.

. . .

I have generally discussed Greg's porn hacking in vague terms. In the next entry, I'm a bit more direct, to create a picture of what Greg does.

The ten-year-old that appeared after I clicked on this photo was fully clothed but sexualized by her makeup and clothes, sitting on a bed and talking. I clicked out instantly. I gave up looking at porn all together at this time, as I didn't want Greg spoofing me any more kids. (Who would have thought he'd plant child porn on FB reels? I suppose such escalation is common to porn hackers).

August 5, 2025. Greg blocked my call to the Oregon Employment Department yesterday--an action that could land him in prison. I have three weeks off now, and I have the right to file. Greg has blocked this call before. Here's his typical setup.

When I called a few times, I found this "User Busy" card on my phone. The initial block gave Greg a moment to set up a fake call that seems successful, with the OED introduction and instructions, but when I'm finally waiting for someone to answer, fake hold music comes on the line. OED has characteristic hold music, but this generic classical was not it. He allowed the real call to play for a moment, then attached the false hold music that went on forever.

I knew it was a fake call, but I let it play for three hours just to show it was a doctored call. A three-hour wait is something we saw during Covid, not now.

Greg has set up false hold music and voicemails before, so that my calls don't go anywhere. I've posted about his phone splicing before, and also shown that he placed a fake voicemail at Eugene Weekly, when he was hacking them.

Greg often blocks applications to "services." On the one hand, he's a secret Texas Republican encouraging personal responsibility, but for the most part he uses that position as an excuse to hack.

According to Barton Family Law, NPDs often use GPS tracking, stealing passwords, and social media blocking to control everyone in their house.

Cameras might be used in rooms with a "trust but verify" justification. A family member might be forced to strip for an underwear inspection to ensure that he or she hasn't recently had sex. Gaslighting and shaming are used to cast the NPD as a victim and the family member as a perpetrator, in all situations. Even small disagreements are seen as acts of murderous disloyalty that must be punished.

Greg believes the whole world is under his fatherly control. He drops into anyone's computer to view emails, private posts, and catch a peek if possible. He tracks people's movements on their phones. He limits or alters internet job searches to show you that you can't see what you want to. In cases of extreme "disobedience," he hacks your family to make those around you unhappy. He spoofs dick pics from your phone so that your dates and others believe you're sending the pics. He will produce psyops noises on your computer to disturb and physically harm you. He will create errors in your manuscripts. He will hack your current publisher or employer. He has hacked my publisher Wipf & Stock and Sunbury Press, accomplishing my removal in the latter case.

Some people he has hacked will show out publicly as Greg's friend. A few years ago, a Seattle Pacific faculty member who was on my email list wrote me this panicked note: "Greg is a friend of mine! He has made an incredible contribution! There's no one else like him!" Hacked people often seem panicked like that.

Since Greg dominates, controls, and terrifies his coworkers, I read this man's testimony as a tortured person's declaration of obedience.

One time, when we were FB friends, Greg posted, "Should I forgive her?" Just that one line. Greg's always wounded, always the victim, another common feeling of NPDs. How could the world not love his deep hunger for abuse? Can't people see his accomplishments and love of God?

Greg likes to believe he has achieved something large and world-changing, and he has: He has developed a system to keep all the world under surveillance and to punish anyone who disagrees with him.

The Cruel Giant Who Sank in the Bog

August 2, 2025. Yesterday I posted that Bukowski's poetry was much finer than his raunchy novels--his poem "The Genius of the Crowd" is gorgeous, perfect--and Greg commented with an avatar named Gary Rowan, who says I have no "well known literature." Recently, elsewhere in this larger post, I mentioned that Gregory Wolfe is going to be a hyperlink in my biography, and my assertion roused the narcissist. Greg wanted to push back.

Gary Rowen is clearly an avatar. Why would this Gary Rowan happen to subscribe to a private FB Bukowski group? How would he happen to have the same view of me that Greg has? If I'm so unknown, why does Gary Rowan know me and have such strong opinions of me, especially when I didn't mention my writing in the post?

It's true my books haven't seen a lot of sales. That's partly due to Greg trying his best to cancel them. He disabled my Amazon account, cut the Antioch Review's FB posts about my books, deleted Down in the River from people's personal websites, and hacked Sunbury Press's publisher so that he released me from my "The Lord's Hacker" contract for no good reason, and etc. I explore these and many other similar actions elsewhere in this post.

Then I became more well-known than Greg wanted. In the coordinated anti-censorship campaign of this post, I was able to reach thousands of people regarding Greg's scary behaviors, with some valuable help.

Since my books enjoy some critical success, I believe they will be known one day as censored books and will live on despite Greg's efforts to cancel them. That's all I hope for. I have no grandiose visions, only the wish that my books are not buried by a tyrant.

People don't like censors. They side with authors who were censored. Therefore Greg's obsession to ruin my career backfired--a benefit I didn't expect, as I didn't know my posts would get passed around as much as they were. But of course I hoped my news would get out there somehow. Half of my posts explore his erasure of me and my works, and his interference with my submissions. The chance that something positive could come from this ten-year nightmare is welcome. Any censored author would rejoice at such a possible benefit, even if doesn't come till long after he's gone.

I hope I discuss the possible resurrection of my work with some humility. It's not guaranteed to happen, but it gives me a measure of hope that I haven't had in a while.

Greg's books sold well due to his position at Image Journal. He received good notice from friends and well-wishers. But their critical success is spotty. In Beauty Will Save the World, he presents several strong introductory essays from Image volumes, but there is no structure to the book. It fails to rise as a narrative, and it reads like a flatline. I read this book after Greg had published me at Slant. I saw the power of the writing, and the weakness of the book, and many reviewers also noticed these conflicting qualities.

I can't be sure if "Beauty," his most well-known book, will live. But I suspect that the world will not tolerate a censorship publisher, porn-hacker, and targetter of children to teach it about finding beauty and saving the world. Nor is Greg fit to discuss the best ways to build character in children through reading. I present my mock review of Books that Build Character in featured posts. It's a bad book up and down.

Greg used hacking as a way to secure power in his little empire, and it was hacking that brought him down. Now that, my friends, would be a great story, about a cruel book-hating giant who sought to control everyone in his kingdom and finally sank in the bog. It would be fit for children and anyone else who has a natural love of justice.

Criminals use these dark webs techniques more than we know, and Greg is more of a criminal than we might know.

I mentioned the woman, a friend of a friend, who claimed that someone had planted a microscopic radio in her nasal cavity [Post deleted. Greg might restore it, but I can't find it now]. From a remote distance, this psychopath could fill her head with shrieks and sounds by moving his joy stick. Who's going to believe that? Nobody. She's obviously crazy! But the FBI believed her and worked to find the villain who did this to her.

Greg is also very high-tech and interested in achieving similar torments. When I was writing "The Lord's Hacker"--a book he didn't want me to write--he repeatedly employed a rhythmic hissing at a certain pitch, and it affected my inner ear. Then he finished it off with a volley of hacking techniques that wore me out and reduced me to an incoherent state and I went to the hospital for five days.

It was an impressive hack, with a rising arc, a climax, and a skillful denouement, almost as if he were laying me out for the night or beyond--in a long box, perhaps.

Greg seems to save the hissing for when he's really angry, such as when I introduced new email addresses to my shoutout page the other day.

He uses this psyops method because it does physical and psychological damage. I've captured the sound on a video recording and posted it in another entry here, but it's hard to experience it through the recording. After all, computers do hiss sometimes. It's normal.

But when my computer awakens to sustained and rhythmic hissing, at times when Greg would be especially angry--like when I was writing a book about him--I witness a meaningful pattern. It's not a normal computer sound. Also, this psyops seems of a piece with his other death-dealing hacks presented here. He's surely one of the evil characters who hunts the skies in the dark webs.

June 26, 2025. Back in 2017, I felt like my "Polemical Literature" essay was a little off when I read it after it was published in the Observer. It seemed to contain items that I had not put in. At the time, I didn't suspect Gregory Wolfe, my hacker, though he had deleted or changed parts of my novel and short story manuscripts. My Observer editor wouldn't have changed anything without telling me first. I had a sense of mysterious uncertainty about the changes, but I moved on from it.

I wrote that people could Google me and find the post on my site, and I had a lot of visits. For a while I continued to post on the Iowa Facebook page and received just as many likes.

But soon my posts on that Facebook page were limited to one or two likes. Then my posts were restricted. I could post but never received likes. Greg can actually limit the number of likes a post gets. He can also cover a post so that it's not visible to anyone. This is part of Greg's gaslighting. He wants me to think that no one is interested.

He has done this on my own Facebook page. He seems to preset the number of likes a post will get. At one point, for about a year, I was getting five likes for every post, and all the likes were from other countries, as if he wanted to avoid Americans hearing word about his behavior.

It seems precious to bemoan your Facebook likes--until you realize that it's your censor who is limiting your voice.

Recently the "infected" post on the Iowa page was deleted. I doubt admin would hunt down that post from so many years ago and delete it. Greg deleted it.

Here is a representative Iowa Facebook post before the censorship began.

He has published almost no women at Slant, and the swapping of my photos with women suggests he believes women are inferior. It's a way of laughing at me, as if to say, "Ha ha, I've replaced you with silly little girls, because that's all you're worth"--something like that. One of my screenshots showed two swapped women's photos next to each other, but he has deleted that.

This has been going on for months.

Greg cares a lot about the concept of a job. He lost his job at Image and feels ashamed about that. But he also lists "artist" or "writer" as his job on LinkedIn, so there must be a crosscurrent of desires running through him. "Academic writer" would be the best description for his avocation. I'm actually an artist and a writer, but he ridicules the part-time jobs I do so that I can write.

Greg's Always Hunting and Hacking

April 13, 2025. I’m staying at my ex's and Greg is hacking her computer. If this video is allowed to go through, you can hear her computer hiss. When Greg realizes I’m videoing it, the hissing dies down. Turn up the volume all the way before you watch it.

December 26, 2024. I ran into Camille, the editor of Eugene Weekly the other day, out front of the magazine's office--the one who volunteered to do an article about my hacking but went silent. She was about to go into the office when I was stopping by to tell her the news about the police referral to the FBI. She seemed quite spooked. She put on a mask and didn't want to make eye contact. When I asked if she'd been hacked, she said, "Nope."

.jpg)

Background: Judge Charles Carlson

Highlights

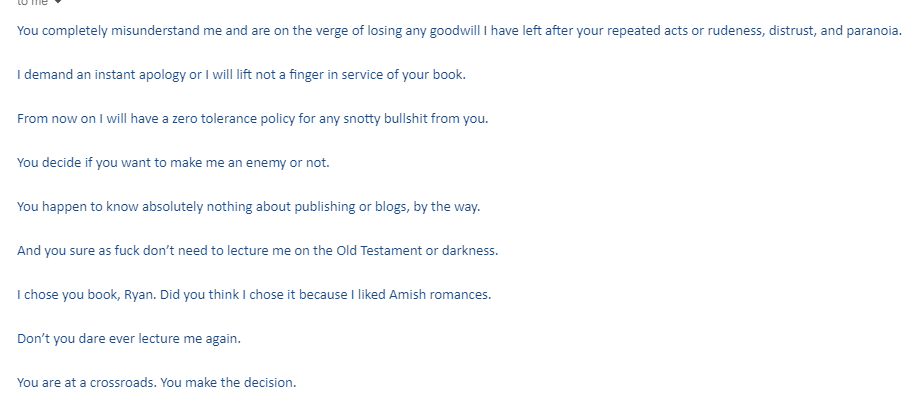

Enemy Email

Illegal Porn

My Hacker Fired for Sexual Harassment

My Hacker is Known for his Dick Pics

Ashley Madison and "The Evil Dead"

These screen shots were deleted from my phone. It's lucky that I had posted them in a private Facebook post.

Manipulates Dating Site

In May 2019 I dated a black woman through a website in Cincinnati when I was divorced. She was a Christian and wanted me to be one, and it didn't work out. In a few weeks, I looked at the dating site again and saw it was all very large black women who were looking only for sex, at least that was all I could see on the site. He seemed to say, Oh you want a black girl? Try one of these.

Sends Infected emails to My Student

Hacks Colleagues and Editors

Spoofs Dick Pics to my Date

Another Editor Hacked

Psyops Noises Issue from My Computer

Hospital Stay

Swaps Digital Info on Caller ID

In November 2023 my hacker switched the name of my doctor and my pest control in my phone's address book, to suggest that I needed to be treated like a pest. He often switches caller ID so I don't know who is calling. My digital world is so full of glitches, I don't believe in glitches anymore.Friend Requests From Kids

Blocks My Phone Calls etc.

Sometimes I can call my doctor's office, but it rings and rings. Or a robot answers and puts me in a cue, but it's not the standard music that my doctor's office plays, and no one ever picks up.

Spoofs My Landlord and Tries to Get Me Kicked out of My House

At the very least, my hacker is certainly not being careful right now. His brand has tanked, and he blames me instead of his behaviors. He's doing things, with greater repetition, that he wouldn't have done last year.

It was Wolfe, pretending to be my son! Yes, things are getting weird. No surprise, he deleted this digital touch exchange, and deleted the screenshot of it later.

Suicide Included in My “Friends”

Constant Social Media Censorship

In November 2023 I joined the Facebook page Beat Poems On the Road and was receiving 500 to 900 likes on my posts. The admin, Steff, got hacked and cut me off. In Facebook pages I frequent, my hacker often uses an avatar to bark at me and complain to the admin about me. If this doesn't work, he hacks them until they drop me. I have experienced this five or six times. In the case of Beat Poems, I believe he couldn't handle that I was getting so much exposure, and he had to put an end to it.

One judge, in 2021, told me, when I mentioned my hacker's porn harassment online, "That's his free speech!"

There is something wrong with our laws on cyber harassment right now. We can't seem to locate a sensible position on the issue. When we police speech online, we tend to target political speech, so we correct that overreach by backing off and allowing ghastly crimes to go unchecked.

If someone sends you death images and porn and then twenty pictures of your son or daughter from your iphone memories, in meaningful and threatening repetition, not even the fiercest Libertarian would say, "Free speech! I love this!"

But I was pleased to hear this judge agreed that his behavior may well be psychotic and dangerous and that the internet is a running ground for criminals. At least she didn't pretend that all is well and that it's free speech.

"Change your passwords." This is advice I've heard from tech people, many who make a lot of money. This advice is also a favorite of cops. Even IT "experts" will tell you that you need to change passwords often. You should change them to guard against low-level types. But advanced hackers use a technique called "forced entry" to bypass passwords. I remember when I was in Pittsburgh I was changing my passwords all the time, and that never worked. Greg may have some program that captures password changes. But don't forget, Russian and Chinese hackers have recently blasted their way into Pentagon computers, despite the most advanced defenses in the world, and owned them at every level. A really good hacker can certainly get into my computer and yours.

At any rate, yes, he gets into Gmail, Facebook, Blogger, LinkedIn--all of the apps.

Regarding his ability to reorder Google content, one person told me years ago, "I doubt he has access." Again, hackers hack. They don't ask for passwords or dig them out of your trash. I have documented that many items rise and fall rapidly on my Google pages. Greg even wallpapered my Google pages with porn descriptions--In 2019 I Googled my name and there they were (see below)--and it took three days for the junk to clear out.

There's a lot of innocence about hacking. But things are changing. More people know what spoofing is now, for instance. The FBI knows that a spoofer owns your phone and can send your pictures of your naked body to your husband's friend, so it looks like you're sending it to flirt. And the FBI no longer says corny, low-level stuff like, "Did you change your passwords?"

If an IT dude who seems smart about defending your computer but has no experience dealing with an advanced hacker--if he tells you "nobody's getting in" and "change your passwords," I hope you'll be a bit skeptical. Be skeptical of me too, but at least I have had some experience with a master hacker, and I've shown fifty-plus pages of real-life hacks. It's true some of it is just based on my word. But most of it is based on alarming screenshots and narrative of my experience.

I don't wish to dismiss all IT people, only to say that most of them aren't ready to defend the Pentagon. But one IT guy I met actually had a lot of experience with hackers. He worked with a lawyer I employed last year. He was familiar with top-drawer hacking. When he looked at my GW post, he said it was obvious that I'm the victim of a crime. The lawyer said the same thing, but they asked for money I didn't have beyond the $700 I had already handed out.

Places Face on My Blog as Warning

March 20, 2024. Greg placed his face on my blog after I posted "A Christian Leader's Life." My blog has always used the picture on the top post for the site picture (after two or three days), no matter how popular a post below it might be. This Moses pic was on my blog for two weeks.

Deleted Blog Followers

Eugene Weekly

March 27, 2024. After I posted "A Christian Leader's Life," the Eugene Weekly editor said she wanted to do an investigative article on Wolfe. When I called days later, I found a generic, robot voicemail and left a brief message. Later in the day it struck me as odd that the voicemail would be generic. He has placed fake voice systems on my phone before.

I left my house, getting away from Wi-Fi, and called again, down the block. This time there was a real voice thanking the caller for contacting Eugene Weekly, but it was closed so I left no message.

Greg has intercepted many of my calls, often just to be a creep, but sometimes to keep me from talking to someone he doesn't want me to talk to.

Eugene Weekly

Questions

I wanted to address any who might believe I have no evidence, simply because I lack an IP or a photograph of my hacker caught in the act. As Judge Charles Carlson told me at the hearing, I have evidence that would be persuasive in civil court, and my assertions raise many questions that point directly to Gregory Wolfe.

For instance, who placed Greg's picture on my blog for two weeks, a threatening gesture, after my post went live? Only my hacker would place his image on my blog.

Who removed the many followers of this blog before I posted "A Christian Leader's Life"? Some other nemesis?

Who deleted the emails from my hacker to me and then restored some of them but not all? Who else had a motive?

Who deleted my email containing the porn descriptions that my hacker used to cover my Google pages, the email I had sent to the scholars? Who else would want to?

Who edited "A Christian Leader's Life" a few times after it went live, to convey a frivolous and unedited and sometimes confusing vibe so that I had to keeping rewriting it?

Who replaced the screenshot of the fake email that contained the iPhone memory?

Who deleted the photo I took of my son sitting in front of his computer? It was wallpapered with my book cover art that my hacker had helped create. My hacker had the motive.

Who is so focused on my son that he has to keep sending me his pictures to convey a threat? Who else deletes his texts? Some other random hacker?

Who demeaned, repeatedly, working class people in fake blogs and on my blog, just as he demeaned the working class background of one of the women who fired him?

Who else would spoof my police report about my hacker, placing my landlord’s name and email and phone on the report?

What else would be interested in my communication about my hacker to the police?

If it was a different hacker, he must have been very sympathetic to Gregory Wolfe and spent a lot of time covering for him and concealing his crimes.

Froze My Site Visit Counter

June 22, 2024. Right after I posted this today, I saw thirty people visited the site right away. Then the counter was turned off. That's Greg's way of staying in charge--again with the censorship. He also turned off my visit counter when I posted the two paragraphs from Poets & Writers last week. He doesn't believe anyone should get notice that's a little better than what he has. He's also angry about that post because he doesn't want to explain why I dumped Slant, especially since he pretended that it was his idea that I left--awkward! [The counter resumed six hours after this post went live].

When I blocked one young prostitute, my screen froze on my phone, but I was able to block the rest on my computer.

June 28, 2024. Greg deleted this polar bear photo from this site and from my desktop today, and I took another screenshot of it. He has deleted other photos related to his harassment concerning my son, as described elsewhere in this document, possibly because he doesn't think that obsessing about someone else's child is a very good look. He would be right.

Some radicals say that Christians are often perverts. It’s more accurate to say that perverts are often Christians. They need an identity behind which to hide. Most perverts understand they can’t live in society as the way they are. Some become Christian leaders. Christian author M. Scott Peck explores this phenomenon in People of the Lie.

This morning when I opened my phone I found that an off-white “card” had been placed over most of the text of our emails. Last year, Gregory Wolfe sometimes placed such cards on the very Word doc of The Lord's Hacker as I was writing it. He never left it there for more than a minute. He was just using one of his myriad hacking tricks and wanted to send the message that he’s in charge.

This time I believe Greg's covering up my emails with the editor communicates that he’s going to cancel my arrangement with the editor, that he’ll ruin it somehow, as he always does.

Greg’s censorship is tricky in several ways. Not only has Greg sent infected emails to publishers in my name—and will likely do so again—but there’s also the psychology of the publisher to consider. Though most publishers find censorship despicable, they also don’t want to walk into controversy or open themselves up to attack by malevolent actors.

It’s easy to look back at beloved writers who were censored and wonder why they were so alone in their fight, like Isaac Babel and Rousseau.

It’s only later, usually after the censored author and his enemies are dead, that supporters seek to publish their censored work. I don’t place myself in that company of luminaries—nor do I see most rejections as censorship—but I do expect fearful silence and cold shoulders from any publisher who learns of the hacking. That’s what Gregory Wolfe wants too. He loves to see his terror result in destroyed relationships and neglected books. He’d burn them if he could. Being a publisher must offer psychological cover for this passion he has for censorship.

All Greg has left is the ability to frighten people. When Orwell imagined the future as a boot stomping on a human face, he surely conjured tyrants like Gregory Wolfe. I hope there are some, like the fighters in the French Resistance, who are willing to take some risks against a true enemy of humankind.

They do everything by the manual. The FBI even has a specific technique of taking phone calls. They pepper the caller with snarky questions and comments. "What's this guy's motivation?" or "I can guarantee he doesn't have any interest in your Facebook page." Then he or she begins the rapid closure of the phone call, talking in the dazzling speed of an auctioneer: "Thank you for calling the FBI. This call will be documented and you are free to follow up with a complaint." And they hang up on you. All intake people do this exactly the same way.

I know they are looking for words like "I'm going to kill you," etc. and that they are trained to dismiss anything about social media or otherwise frivolous concerns. But my hacker, in fact, uses social media and my Google page as a template in which to present child death images, underage porn, a photo of my friend who committed suicide, etc. It's true the FBI is looking for extortion and bodily harm, but my harassment case is horrifying and dangerous, not frivolous, not imagined, not paranoid, and deserves an investigation.

Judges also tend to dismiss almost all hacking claims. I've stood before a few judges who were visibly angry that I even brought a hacking case. Even while newspapers and attorneys say that Russian-style hacking is increasingly common in America, judges and law enforcement respond to this reality by refusing to believe it even exists.

Since this response makes no logical sense, I believe this shutting of the eyes is a psychological reaction. After all, law enforcement has not kept apace with the high-tech criminal hackers. To open up law dockets to hacking cases would be like opening a portal to a howling infinite that would cause headaches for courts, judges, and law enforcement.

And this is why judges and law enforcement regard with anger and distaste the person who brings forward a hacking case. They can't do anything about it! They don't have the tech. Psychologically they have hardened themselves against you, knowing that your possibly reasonable case can't even be considered. You almost become a criminal in their eyes.

As far as the FBI, I believe the only luck I'd have there would be to find an individual agent who thinks outside of the organization. I've been lucky to meet one police officer, one lawyer, and one judge who are indeed able to think independently about this issue, and now I hope to meet one FBI agent. I'm not holding my breath, though.

By the time I knew her, she had mostly normalized. She had taken one of my creative writing classes and we started dating later. When my then-wife Daphne asked her to stop sleeping with me, she wrote that she liked me too much to stop. I was glad, since I was in love with Jane. After all, she and I had both been cheated on. We didn't need to honor those commitments. But we struggled with the affair. One day I was never supposed to contact her again. The next night we'd fly to each other in some city park. Even years later, we weren't supposed to contact each other, but we still made plans to catch up.

In 2013, when I was remarried, Jane wrote that she hoped "we'd always find a way to love each other in some way." My new wife, Becca, was uncomfortable with this contact, and I stayed out of touch with her for a couple of years, until Becca was okay with my catching up with Jane on occasion. There was nothing romantic about my and Jane's contact at this point.

In 2015, Jane told me on the phone that I was "not allowed" to write about anything she'd told me about her husband and the woman he'd had an affair with. She said it was her material. I'd told her I was including some of that story. We kept in loose contact. We were trying to stay out of touch, but we'd exchanged emails and planned telephone calls over the next three years. She was on my email shoutout lists for my first book, and in 2018 she said that was too much. Once again, we decided to stay away, but ended up planning telephone calls.

Her mother told me she was "our little drama queen." She was all over the map in terms of how she perceived a situation, then insisted that she'd had one fixed idea all along.

In 2019 I got divorced. A few months later, in an abject mood, I wrote Jane that I'd always love her, remembering the note she had written me. She showed my email to the CEO of Wipf & Stock, her new boss and my publisher.

It had been foolish to write the email I did, so many years after the note she'd written me about finding a way to love each other. Then she went to work for Gregory Wolfe, after he was fired for sexual harassment--my first publisher and active hacker.

I was surprised she went to work for Gregory Wolfe. Neither she nor I were Puritans. After we had broken up years earlier, we both went through months of haphazard hookups with multiple people, like those recovering from a breakup often do. We were sloppy, stupid, but not cruel.

But I had told her about Wolfe's hacking and sexual harassment, and I supposed she didn't care. Greg's gaslighting of a young intern was a calculated moment of dishonesty and cruelty. It wasn't a sad dalliance that might be forgiven.

In 2022, after I mentioned the woman who influenced Karmina, without naming Jane, on a public Facebook post, I received a rare manic hacking that went on for days. I doubted that Greg would take it on himself to hack me for a Facebook post that didn't name Jane, so I believed that she had complained about it to her former boss, Gregory Wolfe.

I often give updates about characters I'm writing and mention the people who inspired them. Many times I have posted about my first wife, Daphne, who had told Jane to stop sleeping with me. Daphne is a smart Latina poet who attended Reed College. I have also written about Becca, who is all over The Lord's Hacker--she's the exemplar of that book--and who remains a good friend. I have posted about many old girlfriends, wives, friends, and family members, in public and private posts, and none of them scandalous. And Jane's character in Karmina is compelling and sympathetic.

In 2023, I posted a photo of Jane's laptop resting on a cafe table, while referencing Karmina and not naming Jane--the picture was taken in a cafe in summer, and evoked the mood of the book--and again came the savage hacking in the style of Gregory Wolfe.

I have written about many people in magazines as well, with changed names. No one but Jane and Greg has ever implied that I don't have the right to write about my own experience.

On June 21, 2024, a few days after I made public a positive rejection of Karmina, I received a similar brutal hacking--in excess of the usual hacking--and again I believed Jane had told Greg that it wasn't my material to use, and he hacked me like a devil. Why would Greg care if Karmina got rejected somewhere? She must have complained to him again.

Jane has a history of calling strong men as needed, such as when she needed a washing machine and tearfully called her dad. Then she outed him later, by name, as a Trump supporter in an online magazine, as if forgetting her own questionable right-wing past [the article is now offline]. I'm not a Trump supporter, but goodness, leave your dad alone. And I know Greg likes to play the strong, chivalrous Christian leader when he gets a chance, and I bet he likes flexing his hacking muscles for her.

I had emailed Jane about Greg's shocking activities as a hacker--he lives in the very toilet of the world--but she wasn't interested. She commenced her own hacking efforts, though still a Christian. In 2023 I saw she'd covered up one of her letters online that she wrote in support of the man who kidnapped his kids at gunpoint. When I clicked on it, a message read, "your computer is now infected."

I believe I have been hacked about ten times by someone who uses this style of hacking--"your computer is now infected"--and it seems connected to the person who tried to cover up the letter Jane wrote. That would suggest Jane was the hacker.

In 2024, when I clicked on her letter in support of the Christines, it went to a line up of porn pics--a change in tactics. She was using porn now, like Gregory Wolfe, both of them Christians. This seemed to me like Jane's new method of blocking the letter she'd written when she was a member of the cult. I was able to take a screenshot of the letter before it bounced to porn.

I received more "Your computer is infected" hacks. I assumed Jane was communicating that I needed to avoid writing about her.

Only one passage in Karmina explores what I heard regarding Jane's husband and his affair. Fictionalized, it involves a birth and burial scene in a park in Ashland, and since I heard the story and made it fiction, I intend to use it. I already have.

If Jane is working with Greg to censor my book--and sharpening her own hacking tools--she is breaking the law, following her mentor into a dark webs criminal underworld. She might retaliate against me for exposing her, but that's what hackers do. They want to live anonymously in their crimes, and they shriek when the sunlight reveals their behaviors.

When I knew Jane, she was an uncommonly bright, religious church woman with many contradictions. She danced tango, discoursed on the books she read, disciplined her kids with heavy wooden spoons, and made friends with men who could help her financially or otherwise. She was also a warm, inspiring, and impressive person.

However, now and then Jane appears to be drawn to men who are extreme and potentially dangerous, as if such men can step in and provide comfort and assistance on a bad day. She invents narratives about their goodness while she impugns their adversaries, just as she did when she posted about her armed Christian patriot friend, Brian Christine, years ago.

Hi everyone!

I wanted to write you really quick and tell you about a family we

know that is in dire need of help, and especially PRAYER! Their names are Brian and Ruth Christine, they have five girls Bethany, Miriam, Lydia, Olivia and Abbey Rose.