Tropic of Cancer

Henry Miller was a bohemian writer who intended to send shock waves through the English-speaking world. That might explain why his language is sometimes derogatory toward women, the elderly, the highly normative, and many others he encounters. It seems he's actually trying to alienate. At one point, he laughs at the death of a colleague. Another time, he's disturbed by the thought of a baby squirming in a woman's belly.

But he's up to something in his book that isn't readily apparent. He presents a Henry Miller who is far worse than the actual man. In life, for instance, he had a thousand friends, men and women. Once, when he was hungry and poor, he asked several friends if he could eat at their houses once a week. They all agreed. But he never would have received such hospitality if he treated men and women like that.

While writing the book at forty, he included feelings and attitudes that most other writers left out of their books, and challenged the niceties and capitulations that many readers and publishers expected.

His hero Rimbaud encouraged authors to take up a "scummy" appearance and attitude to fight the antiseptic falseness of middle-class morality. Celine, another influence, told the truth in a thousand forbidden ways. Miller writes with these authors at his back.

Baudelaire, Gide, and, later, Genet were also part of this literary school of social combat. This describes part of their work, at any rate. They went out of their way to challenge norms, creating rebellious and sometimes low-life protagonists to strike blows against pious gatekeepers. Genet's glorified young gay criminals and prostitutes were indeed shocking, though he was beloved by literary authors.

For the most part, the French understand that exploration of taboo subjects and "crude" protagonists was part of their method and forgive them, or love them all the more.

Many American readers, on the other hand, who often fail to see the French influences in "Tropic," encounter a book that is inexplicably upsetting, as if it's a document without a context, history, or literary milieu.

Everyone knows that Henry Miller was American, but few know that his books are culturally French. That said, he can't escape his American side that pops up here and there.

Past the rude surface, the book is more inspiring and life-affirming than one might expect. On its first page, the protagonist states, “I have no money, no resources, no hopes. I am the happiest man alive.” One finds similar Whitmanesque pronouncements throughout.

Tropic of Cancer is, in part, an experiment in contradictions, stuffing the pages full of all that is terrible and good about this fictional Henry Miller. He plays a role in the book--the vagabond artist, the womanizer, the streetwise cynic. But here and there in these chapters we find a gentler man, and he was vastly more gentle in life.

Anais Nin recorded the great respect he paid to their friendship over years in her journals. Also, she loved "Tropic."

"Here is a book which, if such a thing were possible, might restore our appetite for the fundamental realities. The predominant note will seem one of bitterness, and bitterness there is, to the full. But there is also a wild extravagance, a mad gaiety, a verve, a gusto, at times almost a delirium. A continual oscillation between extremes . . ."

Henry Miller was a lifelong iconoclast--he wasn't making it up for his books. But years ago, I believed he was a creep who tried too hard to be bohemian. After watching a few of his interviews, I got a sense of this kind and curious writer who was so beloved by those who knew him. After that, I read him in a different light.

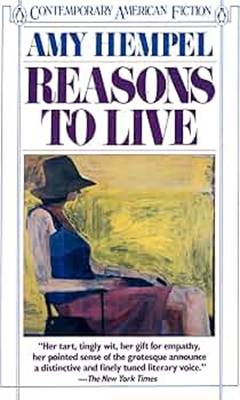

We will read published stories as models. Amy Hempel writes of a woman who abandons a close friend dying of cancer, and confronts the aftermath of her choice.

We will read published stories as models. Amy Hempel writes of a woman who abandons a close friend dying of cancer, and confronts the aftermath of her choice.