“Horses All Over Hell is a heartbreaking new book from a master of modern American fiction.”

—Ernest Hilbert, author of Last One Out, book critic for Wall Street Journal. Dust jacket blurb.

—Mary Clearman Blew, author of Jackalope Dreams and Ruby Dreams of Janis Joplin

And it's clear that the world won't forget about her, though I don't believe she's trying for immortality as a writer. She has too much reading and inquiry in other subjects to think much about herself.

Giovanni's Room

David has lived on the edges of a homosexual milieu in Paris, while conducting an upright heterosexual life. From a car he glimpses many butcher shops, and regards the daily lifestyle of unrestrained sexuality as a brutal reality that he ought to avoid.

But of course he follows Giovanni to his room, and he is never the same. He's repelled--repelled by himself--and he falls in love, and he despises his new lover.

“But it was not the room’s disorder which was frightening; it was the fact that when one began searching for the key to this disorder, one realized that it was not to be found in any of the usual places. For this was not a matter of habit or circumstance or temperament; it was a matter of punishment and grief.”

"People who remember court madness through pain, the pain of the perpetually recurring death of their innocence; people who forget court another kind of madness, the madness of the denial of pain and the hatred of innocence; and the world is mostly divided between madmen who remember and madmen who forget."

I feel stressed when I read such a line of psychological learnedness, as if I have to learn this news immediately. Then I remember to slow down to a speed of deep learning, allowing the words to become part of my own education.

A Farewell to Arms

Though in the beginning Catherine says things like, "There isn't any me anymore. Don't make up a separate me," Frederick speaks in this love language later. Their language might sound treacly or absurd at times, but Hemingway always wanted to locate "the way it was," and this is what being in love sounds like, even if it's sometimes off-putting to those within earshot of the lovers.

But Catherine has real depth. She has experienced loss in the war before meeting Fredrick. She's strong, but also a bit broken and spooked. She imagines herself dead in the rain now and then. She's not crazy, but she feels the pull and dread of her psychology during war, especially.

“I know that the night is not the same as the day: that all things are different, that the things of the night cannot be explained in the day, because they do not then exist, and the night can be a dreadful time for lonely people once their loneliness has started. But with Catherine there was almost no difference in the night except that it was an even better time. If people bring so much courage to the world the world has to kill them to break them, so of course it kills them. The world breaks every one and afterward many are strong at the broken places. But those that will not break it kills. It kills the very good and the very gentle and the very brave impartially. If you are none of these you can be sure it will kill you too but there will be no special hurry.”

When people discuss Virginia Woolf online, there are always a few strident Americans who object to her suicide, as if that action erases her accomplishments. But suicide is tragic, not immoral, in most cases. Since Woolf endured bipolar disorder without the aid of lithium--and suffered a gathering of voices that terrified her in the end--her last years played out with sympathy.

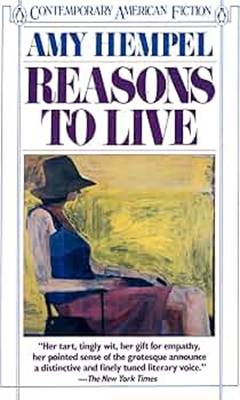

Amy Hempel in the 90s

Reasons to Live is Hempel's best book, oblique, difficult in a way, and each of her stories is absolutely about something that matters. And "In the Cemetery Where Al Jolson is Buried" remains her most popular and anthologized story.

That surprises me because it's such a 90s story--the protagonist looking inward after doing something awful. In our current stories, protagonists tend to look inward only when someone else does something awful.

The central character in "Al Jolson" has abandoned her friend who is dying of cancer--it's hard to descend any lower in the category of friend. But she was too terrified of death to go to the hospital until now. Now she feels ready to face it, everything--death, and her friend she abandoned. She might be ready.

“It is just possible I will say I stayed the night. And who is there that can say that I did not?”

What follows is escape and exhilaration, failure, loss, and regret--and an exploration of her many calamitous fears, as she seeks to understand the depth of her suffering and betrayal.

Amy Hempel was my terrific teacher at the New School in New York City when I went there briefly in the late 90s. We took the train together a few times after class. She had modeled for Italian Vogue, and I resolved not to look at her. She talked about Gordon all the time. Gordon feels this way, Gordon doesn't care for that.

The great editor and teacher, Gordon Lish, had to make any genius he encountered his "creature," like he did with Carver, rewriting stories till they were his own. He rewrote Amy's stories as well. She, too, was Gordon's creature. He had creatures all over the place.

I was telling Amy about the slight, social novels we were forced to read in our seminar. "Oh my God, Gordon hates those books. Why are you reading those?"

But this woman who seemed to consult Gordon on every issue was one of the most original writers around. She was friends with Mark Richard, Tom Waits, Francine Prose, and other famous people in NYC, not just Gordon. In class she told us to get new friends, if necessary, and I thought, I'd pick you, but we were both shy and never got any conversations off the ground.

What a lovely presence she was in class, her voice shaking now and then, her cheeks blushing. Once, she told us something Tom Waits had said: "When I compose at the piano, these hands are like a pair of old dogs, going to all the places they've been before." She often dressed up in slacks and a blouse, conservative outfits. In the office was a photo of her on the board, with the caption "Got Milk?" tacked there.

I liked seeing her shyness. It was one of the things that made me think that I could keep on writing. Amy seemed innocent but her stories were not. They were weighted with experience and personal knowledge that she preferred not to discuss too often, and they were her own stories. Few writers had such an unmistakable style.

The author of the short story collection Horse All Over Hell (Wipf and Stock, 2019) and the novel Down in the River (Wipf and Stock, 2019) talks about his work, inspirations, and characters.

ASO’K: I’d like to ask about Horses All Over Hell, your short story collection released by Wipf and Stock in 2019.

It’s a book of related stories focused upon a family: mother, father, and two sons. You depict problems caused or affected by alcoholism, mental health issues, and religious fundamentalism. These are adult problems, viewed by Cory, a child, who is the elder son. He also does what he can to look after Matt, his younger brother. Why did you choose Cory as the central character?RB: A child inhabits a compelling psychological world. To a kid, a dog might have the power to read minds. A horse on the side of the road might cast a judgmental glance. Cory’s young enough to live in that magic, but old enough to grasp the troubles of his family. He’s an ideal observer.

ASO’K: The setting of Horses is rural Idaho in the early 1990s. Please forgive the cliché question, but may I ask how much of the setting and characters reflect your real-life experiences?

RB: The town of Laroy is, more or less, Lewiston, Idaho. My family lived there in the 70s and 80s. My dad was an alcoholic, but not the wild drunk that Marty is, and my mom was a very traditional, heterosexual Catholic woman who sat with the dying. My dad was an anxiety-ridden parole officer who didn’t talk much except to yell, though he was good-hearted. I was a sports kid and wore my team uniforms at home, watching TV always. My family was hyper-normal, patriotic and God-fearing without question. Once, I tried on my mom’s bra as a joke, and my older brother screamed in fear and tackled me. My mom shouted, “Ryan, this is a Christian household!” My dad was at work. Naturally, I wouldn’t have tried that stunt if he'd been at home.

ASO’K: Cory’s father, Marty, arrives drunk (or at least uselessly hung over) on the morning when he’s supposed to be coaching Cory’s baseball team practice, then again when he’s supposed to be coaching them for a game. Cory’s mother Joanna has quit drinking and found religion, but sees imposing her religious views on her family as a solution to their problems, and is sycophantically desperate for the approval of the more affluent and socially prestigious members of her church group. What’s the biggest thing preventing Marty and Joanna from fixing what’s wrong with their lives? If they appeared to you and asked for advice, what would you tell them?

RB: I understand your temptation to wonder about this. But I say literature isn’t about solving problems. It’s about presenting problems. After all, we follow character trajectories that make sense, based on psychological realities. I’d feel content leading a character to prison if I understood he had to go there because of the story’s urgencies. I’d feel sad but I wouldn’t try to fix his life or anything like that.

Regarding Joanna, I feel sympathetic toward her. She is troubled by anxiety, depression, and suicidal thoughts. She has quit drinking and needs help. Since she’s speaking from pain and not judgement, I don’t get irritated by her reading the Bible to her kids, the way I might in a more self-righteous context. She’s deeply unhappy in Laroy, but church is the only game in town. She seeks to act like the other mothers because she has suffered a loss of confidence during her depression. She’s my favorite kind of Christian—deeply flawed, on the edge, trying to stay alive. The woman she meets, Lucy, the Native-American, is a similar kind of woman, though farther down the road in her sobriety. Later in the book, Joanna locates strength and toughness, partly due to Lucy’s influence. Where Joanna ends up is far more important than where she is at the start.

ASO’K: Birds seem to be a major motif in Horses All Over Hell. Marty, the father, expresses his dislike of large gatherings of birds. What do the birds represent? Other motifs, it seems to me, are the river and the horses of the title.

RB: My favorite metaphor is one that feels meaningful and right but is somewhat out of grasp. The birds resist explanation because characters speak of them differently. The metaphor changes depending on who’s exerting psychological pressure on it. Therefore, it wouldn’t do to nail it down too much. But I will say that I love the mystery of the image and I think it’s right on the money.

Regarding the horses, I suppose they represent disaster and chaos in the book. Of course, there’s got to be a dash of Revelation in the title too, but I wouldn’t make too much of it.

ASO’K: I’d also like to ask about Down in the River, your novel published by Wipf and Stock in 2014. The protagonist, teenager Lyle Rettew, commits an incredibly drastic act in attempting to come to terms with the recent suicide of his twin sister. If you would consider mentioning it to be a spoiler, we can keep mum about it, or mention it openly if you prefer. Anyway, it’s rather macabre, and truly unconventional. Can you describe how this idea came to you?

RB: When Lyle robs a mausoleum, he is flying on his mania, and therefore believes he’s doing something good. Of course, it is terrible and macabre. Lyle’s action is mitigated, though, when the reader understands he’s acting out of love for his sister, in his own cracked manner. Though his sister’s remains are in Idaho, and he’s in Eugene, Oregon, he associates this body he steals with his lost best friend and twin, Lila.

He meets Rosa, a Latina who says about him, “Oh, you’re not quite right,” but knows he’s a good person at the same time. They happen into some speed. She becomes disturbed when she discovers what he’s carrying around in his backpack, but he explains it again and again—when she’s alternately high and tired—and she stays with him.

Although there’s not much sympathy for bi-polar people in the world right now, especially ones who rob mausoleums, I felt very tender about Lyle. Once, Lyle stands up for a goose who hits the top of a bridge while flying. It sits on the pedestrian walkways below, very dazed. Lyle guards the bridge and forces two kids to turn around, so they won’t frighten the goose.

Rosa says to him, “You’re like some kind of protector.”

But some readers won’t tolerate a sympathetic story about a grave robber. That’s okay. I wasn’t trying to please everyone.

Pittsburgh's City Paper "Arts Feature" Interview:

https://www.pghcitypaper.com/arts-entertainment-2/cp-catches-up-with-newly-arrived-novelist-ryan-blacketter-1851057/

Paste Magazine's interview with Ryan Blacketter: "The human story is a fairly dark one with painful and dangerous impulses that we all have. And that's coupled with a fortress-like psychology that most people have, protecting them from the awareness of the fact that they are part of this human experience." https://www.pastemagazine.com/books/drinks-with/drinks-with-author-ryan-blacketter/

Fiction Writers Review: "What makes this novel so warm and heartbreaking despite its gruesome material is that all the characters are driven by their love and concern for each other." Click here to read the entire review:

The Rumpus: "[Down in the River] casts us deep into a haunting, crystalline forest of ice-lit trees, broken streetlamps . . . a place where a kind of inner wilderness has crept back through the city, where the lights of passing trains, the reflections of windows and the 'cry of night birds' appear intermittently like forms of meaningless chaos or secret signs." https://therumpus.net/2014/11/down-in-the-river-by-ryan-blacketter/

Quivering Pen Review:

http://davidabramsbooks.blogspot.com/2014/10/slipping-into-skin-down-in-river-by.html

http://www.largeheartedboy.com/blog/archive/2019/07/ryan_blacketter.html

"I was completely enthralled by this haunting, page-turning novel. The disturbing events, the evocative landscape, and the chaos of mental disorder self-medicated by drugs and rebellion are all rendered in humanizing, beautifully-rendered realism."

--Wayne Harrison, The Spark and the Drive

"Down in the River is a startling, disturbing, and ultimately entrancing novel, a fever dream that astounds and never sits still for a moment, breathlessly played out in the sad twilight between the innocence of childhood and the despair of age, life lived on the last edges of love and loyalty strained to their limits."

--Ernest Hilbert, author of Caligulan

"Blacketter has created an outsider story of adolescence that left me wanting to travel more with his characters; I felt connected to them as they opened my eyes to new forms of chaos."

--Max Wolf Valerio, author of The Criminal: the invisibility of parallel forces.

—Mary Clearman Blew, author of Jackalope Dreams and Ruby Dreams of Janis Joplin

--Arthur O'Keefe, author of The Spirit Phone

“Lyle is clearly disturbed, but Blacketter never lets him become a caricature, never lets his mental illness cloud his personality or override his humanity. Like Dubus’s characters, even his most terrible deeds are driven by noble impulses and understandable grief.”

"A remarkable, darkly startling and endearing debut novel . . . As Lyle’s quest unfolds with messy inevitability, I am rooting for this young man, I am living as this young man, I am learning to feel as skewed and caring as Lyle does. And what a pleasure this is, and what great inspiration to a fellow writer the experience of Down in the River is. I cannot recommend this novel enough."

"A strange, haunting journey across the shadowy landscape of grief and longing. To our good fortune, Ryan Blacketter is a heroic guide into this exploration of the mysterious workings of the human heart . . . This is a brave first novel from a writer to be watched."

When the Hippies are Gone

We’ll need a renaissance to stand our lives with iPhones and AI. It’s harder to read, harder to write. As if there is some demented spirit in tech that closes the books we are reading. It must be once a month that I read about an AI chat inviting someone to commit suicide. Evil people can do that too, but it’s best to avoid them.

Creative rebirths occur after long periods of darkness. At such times, many thousands of people at once, especially young people, decide to go inward and live creative lives. In the 60s people left their jobs to live on farms with friends, to write poetry or play music.

An invitation to return to the 60s can be corny, conjuring Google stock images of peace signs and round glasses. But when I was a kid growing up in Eugene, many of my friends’ parents were hippies. Many had natural smiles, and it wasn’t just the pot. They had found something successful.

Most of them rented apartments or houses, built cabinets or worked at canneries or places like Genesis Juice. They had parties at friends’ houses in the woods, playing music together, and the kids joining in. They were easy inside, most of them, and deeply friendly. They had something.

When they were kids in the 50s, their parents burned to succeed in view of their neighbors. They saw their fathers’ rage play out over years as they worked at corporations and nothing vital came of the hard work except a healthy lawn. They heard their mothers speak words that only hinted at the meaning below, cheerful greetings that echoed in the mind as oblique pleas for help. Or they had similar experiences common to the American landscape then.

In America, a million kids grew up as outward creatures. Commanded to seem happy and correct, to avoid their inward selves, they developed a sickness, and they didn't know this sickness meant they were creative. They wanted to speak and hear true words and to create objects of beauty.

Old Eugene was a hippie town in the 80s. At 5th Street Market, there was a rear seating area where hippies and alternative kids drank coffee and smoked. People read and discussed authors like Richard Brautigan and Susan Sontag. Though I wasn't much of a reader, I liked The Catcher in the Rye. That was a favorite book among the hippies. It explores a kid who insisted on being who he really was.

Around 2010, in Eugene, I'd see a few old hippies driving their old Subarus or Hondas. My friends and I liked them for their graceful staying power, their ability to pursue a lifestyle while being poor or middle class. They were good luck for those of us who were trying to make it happen with our music or writing. But then the hippies went away and a different kind of people came to town.

By 2020, most of the younger creative people I knew in Eugene and Portland had given up their art for tech jobs. It wasn’t simply because life was more expensive. It was because creativity wasn’t respected anymore.

I know why people from Los Angeles County seem to care only about money. I know why they're afraid of people who don't seem like them. They grew up around dangerous wanderers in the streets. They had to be careful who they talked to. Owning a home in a good neighborhood meant safety for their families.

In addition, there really are some dangerous people in Eugene. And some of them look like hippies, such as young people with skinny dogs. "Give me a fucking fiver. You've got it. Come on, I'm a hippy. I'm trying to feed my dog, bitch. Hey!"

But it's the people wearing Giorgio Armani ski jackets who worry me the most. They're afraid of me because I look poor in my winter coat I bought at Target, but I'm afraid of them, too.

Few things kill the arts like an invasive wealth culture that doesn’t respect creative life. You think you have to start writing romance books and cash in--it's the only way to have respect. There's no place for you, the way you are, as is.

But I won't write romance novels. I'm writing for those who are coming later. They're the people of the next renaissance. They probably aren't born yet, but they are on the way.

Henry Miller was a bohemian writer who intended to send shock waves through the English-speaking world. That might explain why his language is sometimes derogatory toward women, the elderly, the highly normative, and many others he encounters. It seems he's actually trying to alienate. At one point, he laughs at the death of a colleague. Another time, he's disturbed by the thought of a baby squirming in a woman's belly.

But he's up to something in his book that isn't readily apparent. He presents a Henry Miller who is far worse than the actual man. In life, for instance, he had a thousand friends, men and women. Once, when he was hungry and poor, he asked several friends if he could eat at their houses once a week. They all agreed. But he never would have received such hospitality if he treated men and women like that.

While writing the book at forty, he included feelings and attitudes that most other writers left out of their books, and challenged the niceties and capitulations that many readers and publishers expected.

His hero Rimbaud encouraged authors to take up a "scummy" appearance and attitude to fight the antiseptic falseness of middle-class morality. Celine, another influence, told the truth in a thousand forbidden ways. Miller writes with these authors at his back.

Baudelaire, Gide, and, later, Genet were also part of this literary school of social combat. This describes part of their work, at any rate. They went out of their way to challenge norms, creating rebellious and sometimes low-life protagonists to strike blows against pious gatekeepers. Genet's glorified young gay criminals and prostitutes were indeed shocking, though he was beloved by literary authors.

For the most part, the French understand that exploration of taboo subjects and "crude" protagonists was part of their method and forgive them, or love them all the more.

Many American readers, on the other hand, who often fail to see the French influences in "Tropic," encounter a book that is inexplicably upsetting, as if it's a document without a context, history, or literary milieu.

Everyone knows that Henry Miller was American, but few know that his books are culturally French. That said, he can't escape his American side that pops up here and there.

Past the rude surface, the book is more inspiring and life-affirming than one might expect. On its first page, the protagonist states, “I have no money, no resources, no hopes. I am the happiest man alive.” One finds similar Whitmanesque pronouncements throughout.

Tropic of Cancer is, in part, an experiment in contradictions, stuffing the pages full of all that is terrible and good about this fictional Henry Miller. He plays a role in the book--the vagabond artist, the womanizer, the streetwise cynic. But here and there in these chapters we find a gentler man, and he was vastly more gentle in life.

Anais Nin recorded the great respect he paid to their friendship over years in her journals. Also, she loved "Tropic."

"Here is a book which, if such a thing were possible, might restore our appetite for the fundamental realities. The predominant note will seem one of bitterness, and bitterness there is, to the full. But there is also a wild extravagance, a mad gaiety, a verve, a gusto, at times almost a delirium. A continual oscillation between extremes . . ."

Henry Miller was a lifelong iconoclast--he wasn't making it up for his books. But years ago, I believed he was a creep who tried too hard to be bohemian. After watching a few of his interviews, I got a sense of this kind and curious writer who was so beloved by those who knew him. After that, I read him in a different light.

No comments:

Post a Comment