The presentation suggests that the closure was due to Greg's absence. Of course, Greg wanted to give that impression. And there is an obvious intention to communicate that it's still closed! You have to select an ambiguous link at the bottom ("details of closure") to see that the journal is now open.

[I had to click on "Details of closure" to see that Image "did not close." This information was not on the main page.]

August 20, 2024. For many years, Gregory Wolfe has made alterations of spelling and grammar in my stories and books before I send them out . . .

[Note: 4/27/25]. This screenshot has recently been blurred by Greg the censor (and the original email deleted) because it shows that the editor invited me to submit. She says, "Please send me any of your writing you'd like me to consider for hobart." She also says she'd love to hear what I've done with my writing since graduating from Iowa. Another Editor Hacked

In October 2023 I was going to submit a story to my friend who runs a literary journal in Serbia. She had asked me to send a story, and seemed disappointed when I had told her I couldn't separate a story from my published book. Then I found two stories for her. In the exchange below, she reveals that she was being hacked.

Remind me never to call these weenies when a French Resistance type of situation appears in America. Men and women of the French Resistance risked torture at the hands of Klaus Barbie. The publishers and editors who showed enthusiasm in seeing my work, but then went silent when they were hacked--too afraid even to send me a rejection note--couldn't handle getting hacked for ten minutes.

But I'm enormously grateful to those who have shown up to this fight.

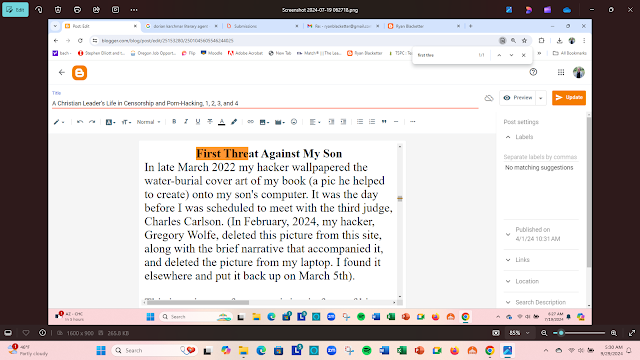

Greg Places His Face on My Blog as Warning

March 20, 2024. Greg placed his face on my blog after I posted "A Christian Leader's Life." My blog has always used the picture on the top post for the site picture (after two or three days), no matter how popular a post below it might be. This Moses pic was on my blog for two weeks.

Spoofs Dick Pics to my Date

December, 2022. I met a Latina who managed a bowling alley at Valley River Center. We planned to go out on a date.

The screenshots were deleted from my phone. It's lucky that I had posted them in a private Facebook post.

June 26, 2025. Back in 2017, I felt like my "Polemical Literature" essay was a little off when I read it after it was published in the Observer. It seemed to contain items that I had not put in. At the time, I didn't suspect Greg, though he had deleted or changed parts of my novel and short story manuscripts. My editor wouldn't have changed anything without telling me first. I had a sense of mysterious uncertainty about the changes, but I moved on from it.

Questions

I wanted to address any who might believe I have no evidence, simply because I lack an IP or a photograph of my hacker caught in the act. As Judge Charles Carlson told me at the hearing, I have evidence that would be persuasive in civil court, and my assertions raise many questions that point directly to Gregory Wolfe. (Carlson said this in 2022, when I had less evidence).

For instance, who placed Greg's picture on my blog for two weeks, a threatening gesture, after my post went live? Only my hacker would place his image on my blog.

Who removed the many followers of this blog right before I posted the Gregory Wolfe post? Some other nemesis?

Who edited this post many times after it went live, to convey a frivolous and unedited and sometimes confusing vibe so that I had to keeping rewriting it?

Who deleted the photo I took of my son sitting in front of his computer?

If it was a different hacker, he must have been very sympathetic to Gregory Wolfe and spent a lot of time covering for him and concealing his crimes.

_________________________________________

(after 5, the post continues 1 through 4)

The presentation suggests that the closure was due to Greg's absence. Of course, Greg wanted to give that impression. And there is an obvious intention to communicate that it's still closed! You have to select an ambiguous link at the bottom ("details of closure") to see that the journal is now open.

[I had to click on "Details of closure" to see that Image "did not close." This information was not on the main page.]

Please review my first positive and accurate AI search below, and the false AI searches that came after it, once Greg saw that I had searched myself on AI. Compare the positive statements about Down in the River with those that came later.

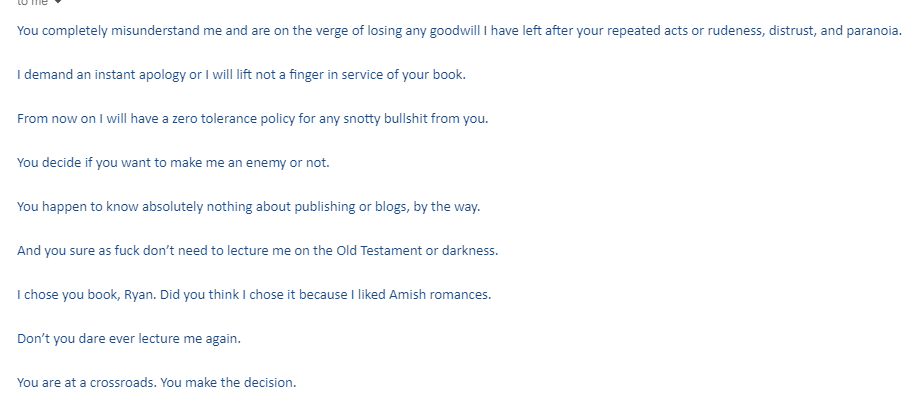

Publisher Lawrence Knorr accepted "The Lord's Hacker" in September 2024. A couple of months later, he told me on the phone that the Christian leader was interesting. I asked him if the hacking moments seemed too fantastic, and he told me he believed they could be done.

Five months after that, he released me from my contract. He said that I had complained too much about my editor's rewriting my characters and the staff had lost their generosity toward me. They insisted they were only trying to "help" my book.

He obviously arrived at an about face, and I believe he had Greg's help in that. Also, a publisher writing a negative review about a character in an email that promised a termination letter, seven months after the book's acceptance, seems unaccountably strange--especially since the publisher had read the book before and claimed to like that character.

I believe Greg hacked Lawrence, just as he has hacked so many other publishers, and so the latter was forced to adjust his feelings and attitudes about that character. He must've figured Greg was reviewing our emails, and he wanted Greg to leave him alone.

The one commonality hacked people share is that they say very strange things in their rubber-legged, shaky-fingered panic.

He had the motive to delete all of my blog followers, disable comment functions, delete some of my posts that focused on Greg targeting my child, delete my emails about Greg, delete emails his friends sent me, delete emails that had attachments of screenshots of his work. He had the motive to delete police reports I’ve filed about him, delete records before I requested a restraining order, delete my emails to Oregon Judicial Watch. And he had the motive to cripple my Amazon author page right after Lawrence Knorr at Sunbury Press accepted The Lord's Hacker (a book about Gregory Wolfe). When that wasn't good enough, he hacked Knorr, resulting in a dismissal of my contract, and on and on ("Greg Hacks Another Publisher"). And these are only the hacking incidents in which Greg was saving his own butt!

Criminals say that if you want to kill someone you should kill some random person you don’t know. Then the clues won’t point at you. That’s true for choosing your hacking victim as well.

Last night I started watching "The Wolf of God," when I discovered the subtitles were off. When I tried to turn them on, the screen froze, then I was kicked out. I tried again and was thrown out. Then I discovered the subtitles were on, but the screen was black. (Two screenshots below). It was definitely a Gregory Wolfe operation.

Like some of the very bad characters I mentioned above, Gregory Wolfe has a surface belief in the church. He has devoted a lot of time to writing about his faith, but he compartmentalizes his evil behaviors, justifies them as holy acts in defense of the church, and probably even forgets about them sometimes. He wants to believe that he's a true son, and so he works fast to disable or hush up any negatives about the one true faith. In this way, he proves to himself that he really is working on the side of the church. I doubt he has any trouble justifying the illegal porn, child targeting, and all the rest of it.

It's also strange that he'd believe that covering up evil in the church is somehow working on the side of the church. Since that makes no sense, I think he simply decides to believe it, while forgetting that the evil people are in fact enemies of the church, and that he's one of them.

This photo presents a smiling and successful Gregory Wolfe, editor of Image Journal. He's got the Christianity Today vibe. He looks warm here, and probably wants to fit in with normal Christian culture to make his brand attractive. I know he had narcissistic personality disorder then, but at this time his illness remained hidden.

In 2022, only one of the study guides showed the midterm essay prompt, but most of it was bot language, beeps and bops, with my name or the name of the short story appearing. Then it turned into a student business essay at the bottom of the page.

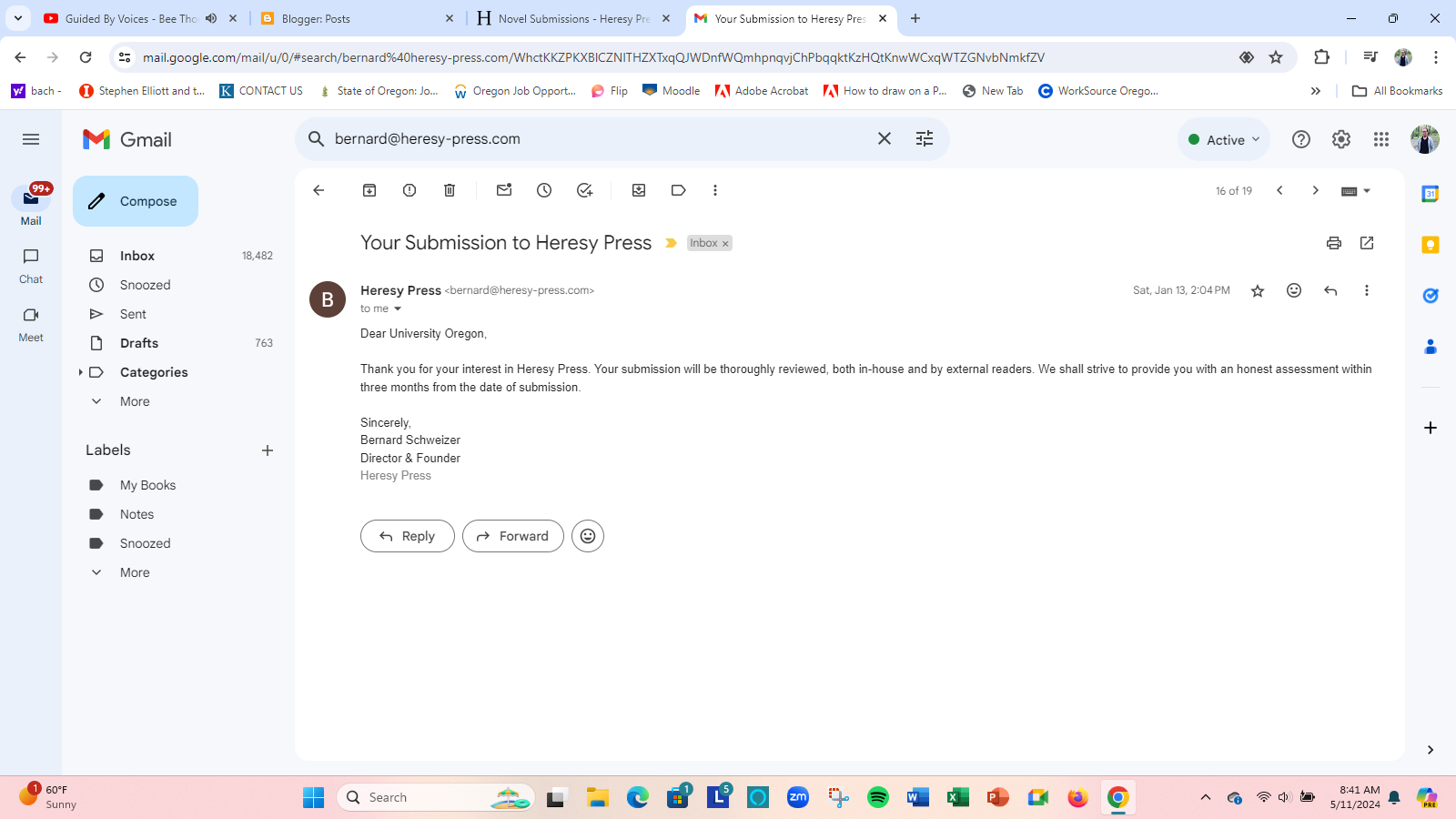

In 2023 Barnard Schweizer, editor of Heresy Press, invited me to submit a book. We hit it off, agreed on a lot of things, and sent occasional friendly emails. Then I made the mistake of telling him I had a hacker, since I figured he'd get hacked anyway if he accepted my book. I thought he might bristle at the censorship and stand up to it. Part of his mission involves standing up for free speech. But he went gloomy and wasn't interested anymore. This is a different case, since I was the one who mentioned it, but I figured telling him directly was my only chance. I don't know if he was hacked.

In 2023 Lara Dodds, English chair at Mississippi State, was warm and friendly in our phone conversation. She believed she could find some online classes for me. During our next conversation, the following month, she was distant and rude. She had no classes--a complete switch in tone--and there was no invitation to apply again. Such things happen, but when they are always happening, it feels very suspicious. It was the severe change in tone that was telling. I know that class availability can change in a department.

Margaret Perrow, English department chair at Southern Oregon University, emailed in 2022 that she was sure she could find a couple of classes for me. She complemented my resume and wrote back a hasty sorry, no jobs, and she would be in meetings for a month etc., adios forever. She seemed to have the panic that hacked people tend to have.

In 2022, the assistant of publisher Dennis Stovall, at Ooligan Press, invited a manuscript because I was friends with one of their authors. Then I received a rejection without comment. Since she invited the manuscript, I counted the lack of a single greeting in the rejection to be highly unusual and a likely hack. Publishers write back when rejecting a book that they invited, at least to say it's not a good fit, best of luck. Hacked people know they can't be in communication with me at all.

In 2022 an English chair in Ohio whose name I can't locate, because we only spoke on the phone, told me my experience sounded amazing. She looked at my site. She said they had ten positions opening up the next term, and advised me to apply immediately. When I applied and hit submit, there was no "success" note. The application simply disappeared--a common story because Greg deletes many of my applications. I called the chair and spoke to her secretary, who told me that none of those ten jobs were open. They had all been filled since the previous day.

Again, I understand the terror of a hack. I've felt it myself. But it's time to understand that hacking is a form of censorship--or a criminal nudge in a hiring decision--and remaining still and silent amounts to working hand in hand with a censor and a criminal. It's impossible to bemoan censorship in one case and capitulate to it in another. Things might change the more we learn about the Dark Web world of Russian-style porn hackers.

This is how OED hold music actually sounds:

At this time, Greg figured out how to hack Facebook. He actually reduced the number of likes I received for my Fiction Titles page--deleted likes that were already there--and I saw that he was dropping the count below his own number of likes.

He also reduced the number of likes I'd get for posts, and he wanted me to see that he was doing it. One year, all of my posts received five likes, every last one, and most of them from other countries. In this way he prevented anyone in America seeing my posts about him.

Then he pushed me into the hospital after a dreadful hacking episode that I have discussed. When I got out, he placed the profile picture of my friend who committed suicide the previous year onto my list of FB friends profiles. He placed it in three different positions so that I'd know it was him doing it.

He continues to position this profile. When I looked this morning, it was there. Michael Friedline is on the bottom right.

Sure enough, I received an email from social security within a few hours of my knock-down note. I applied to social security in 2024 and received my rejection in March 2024. That was the last email I had received before this one. They don't keep you on the email list after you've been rejected.

August 13, 2025. Determining the accuracy of a hack isn't an exact science. Sometimes I know what happened right away, and I continue to know what happened. Other times I decide a post is weak or it doesn't illustrate what I had thought, and I cut it.

Regarding Sunbury Press, at first I believed I was simply let go from my contract, and I didn't think about it for a couple of months. Then, out of the blue, several facts presented themselves to make me certain that Greg had hacked the publisher. Your mind can work on an issue while you're not thinking about it, of course. Those posts that take a little time are often the most illustrative.

In other posts, I simply believe Gregory Wolfe did it. He has a history of sending me porn, for instance, and I know that he has sent other people porn. In 2018 I found a fake Gregory Wolfe Facebook account that had a banner full of penises. I discuss this elsewhere. Whoever made that account knew about Gregory Wolfe's dick pics. I came to know about them personally five years later when he spoofed pics to my date via my phone.

That might not add up in criminal court every time, without an IP. But as Judge Charles Carlson told me, it could add up in civil court, where a "preponderance of the evidence" test is used. That's the test I do my best to follow here. I'm not a lawyer, but I try to present the reasonableness of my assertions in my own layman's way.

When this post first went online, Greg's face appeared on my blog in warning. All my blog followers were deleted. Comments were disabled. And the post went offline. Only Greg had the motivation to control this post about him, and he executed the attack on multiple levels, within two or three days. The connections are obvious and persuasive, despite the lack of an IP. This satisfies the preponderance of the evidence test.

In other cases, patterns are revealed. Greg has sent many death images and many pictures of my son. Since I know he likes to create terror with illegal porn, I extrapolate the same motivation when I receive child death images and other death images of old friends who are actually dead. I know I don't have two hackers, one for porn and one for child death. It's Greg doing both of those.

It's fascinating that Greg doubles down on his hacking when he's been exposed. I believe he started hacking as a way to scare his enemies and protect his brand, but now his motivation has devolved into pure ego. He's like an insane, dying general lying in the desert outside of a village, shooting at anything that moves--women going to the well, children playing soccer, his own men. There's no point to it anymore. He just wants blood.

. . .

I have generally discussed Greg's porn hacking in vague terms. In the next entry, I'm a bit more direct, to create a picture of what Greg does.

The ten-year-old that appeared after I clicked on this photo was fully clothed but sexualized by her makeup and clothes, sitting on a bed and talking. I clicked out instantly. I gave up looking at porn all together at this time, as I didn't want Greg spoofing me any more kids. (Who would have thought he'd plant child porn on FB reels? I suppose such escalation is common to porn hackers).

Take a look at the Observer app on my first Google page. That essay is still named "Polemical Literature." But the same essay, on my Google page seven, is now titled "ZZ Packer."

August 5, 2025. Greg blocked my call to the Oregon Employment Department yesterday--an action that could land him in prison. I have three weeks off now, and I have the right to file. Greg has blocked this call before. Here's his typical setup.

When I called a few times, I found this "User Busy" card on my phone. The initial block gave Greg a moment to set up a fake call that seems successful, with the OED introduction and instructions, but when I'm finally waiting for someone to answer, fake hold music comes on the line. OED has characteristic hold music, but this generic classical was not it. He allowed the real call to play for a moment, then attached the false hold music that went on forever.

I knew it was a fake call, but I let it play for three hours just to show it was a doctored call. A three-hour wait is something we saw during Covid, not now.

Greg has set up false hold music and voicemails before, so that my calls don't go anywhere. I've posted about his phone splicing before, and also shown that he placed a fake voicemail at Eugene Weekly, when he was hacking them.

Greg often blocks applications to "services." On the one hand, he's a secret Texas Republican encouraging personal responsibility, but for the most part he uses that position as an excuse to hack.

According to Barton Family Law, NPDs often use GPS tracking, stealing passwords, and social media blocking to control everyone in their house.

Cameras might be used in rooms with a "trust but verify" justification. A family member might be forced to strip for an underwear inspection to ensure that he or she hasn't recently had sex. Gaslighting and shaming are used to cast the NPD as a victim and the family member as a perpetrator, in all situations. Even small disagreements are seen as acts of murderous disloyalty that must be punished.

Greg believes the whole world is under his fatherly control. He drops into anyone's computer to view emails, private posts, and catch a peek if possible. He tracks people's movements on their phones. He limits or alters internet job searches to show you that you can't see what you want to. In cases of extreme "disobedience," he hacks your family to make those around you unhappy. He spoofs dick pics from your phone so that your dates and others believe you're sending the pics. He will produce psyops noises on your computer to disturb and physically harm you. He will create errors in your manuscripts. He will hack your current publisher or employer. He has hacked my publisher Wipf & Stock and Sunbury Press, accomplishing my removal in the latter case.

Some people he has hacked will show out publicly as Greg's friend. A few years ago, a Seattle Pacific faculty member who was on my email list wrote me this panicked note: "Greg is a friend of mine! He has made an incredible contribution! There's no one else like him!" Hacked people often seem panicked like that.

Since Greg dominates, controls, and terrifies his coworkers, I read this man's testimony as a tortured person's declaration of obedience.

One time, when we were FB friends, Greg posted, "Should I forgive her?" Just that one line. Greg's always wounded, always the victim, another common feeling of NPDs. How could the world not love his deep hunger for abuse? Can't people see his accomplishments and love of God?

Greg likes to believe he has achieved something large and world-changing, and he has: He has developed a system to keep all the world under surveillance and to punish anyone who disagrees with him.

The Cruel Giant Who Sank in the Bog

August 2, 2025. Yesterday I posted that Bukowski's poetry was much finer than his raunchy novels--his poem "The Genius of the Crowd" is gorgeous, perfect--and Greg commented with an avatar named Gary Rowan, who says I have no "well known literature." Recently, elsewhere in this larger post, I mentioned that Gregory Wolfe is going to be a hyperlink in my biography, and my assertion roused the narcissist. Greg wanted to push back.

Gary Rowen is clearly an avatar. Why would this Gary Rowan happen to subscribe to a private FB Bukowski group? How would he happen to have the same view of me that Greg has? If I'm so unknown, why does Gary Rowan know me and have such strong opinions of me, especially when I didn't mention my writing in the post?

It's true my books haven't seen a lot of sales. That's partly due to Greg trying his best to cancel them. He disabled my Amazon account, cut the Antioch Review's FB posts about my books, deleted Down in the River from people's personal websites, and hacked Sunbury Press's publisher so that he released me from my "The Lord's Hacker" contract for no good reason, and etc. I explore these and many other similar actions elsewhere in this post.

Then I became more well-known than Greg wanted. In the coordinated anti-censorship campaign of this post, I was able to reach thousands of people regarding Greg's scary behaviors, with some valuable help.

Since my books enjoy some critical success, I believe they will be known one day as censored books and will live on despite Greg's efforts to cancel them. That's all I hope for. I have no grandiose visions, only the wish that my books are not buried by a tyrant.

People don't like censors. They side with authors who were censored. Therefore Greg's obsession to ruin my career backfired--a benefit I didn't expect, as I didn't know my posts would get passed around as much as they were. But of course I hoped my news would get out there somehow. Half of my posts explore his erasure of me and my works, and his interference with my submissions. The chance that something positive could come from this ten-year nightmare is welcome. Any censored author would rejoice at such a possible benefit, even if doesn't come till long after he's gone.

I hope I discuss the possible resurrection of my work with some humility. It's not guaranteed to happen, but it gives me a measure of hope that I haven't had in a while.

Greg's books sold well due to his position at Image Journal. He received good notice from friends and well-wishers. But their critical success is spotty. In Beauty Will Save the World, he presents several strong introductory essays from Image volumes, but there is no structure to the book. It fails to rise as a narrative, and it reads like a flatline. I read this book after Greg had published me at Slant. I saw the power of the writing, and the weakness of the book, and many reviewers also noticed these conflicting qualities.

I can't be sure if "Beauty," his most well-known book, will live. But I suspect that the world will not tolerate a censorship publisher, porn-hacker, and targetter of children to teach it about finding beauty and saving the world. Nor is Greg fit to discuss the best ways to build character in children through reading. I present my mock review of Books that Build Character in featured posts. It's a bad book up and down.

Greg used hacking as a way to secure power in his little empire, and it was hacking that brought him down. Now that, my friends, would be a great story, about a cruel book-hating giant who sought to control everyone in his kingdom and finally sank in the bog. It would be fit for children and anyone else who has a natural love of justice.

Criminals use these dark webs techniques more than we know, and Greg is more of a criminal than we might know.

I mentioned the woman, a friend of a friend, who claimed that someone had planted a microscopic radio in her nasal cavity [Post deleted. Greg might restore it, but I can't find it now]. From a remote distance, this psychopath could fill her head with shrieks and sounds by moving his joy stick. Who's going to believe that? Nobody. She's obviously crazy! But the FBI believed her and worked to find the villain who did this to her.

Greg is also very high-tech and interested in achieving similar torments. When I was writing "The Lord's Hacker"--a book he didn't want me to write--he repeatedly employed a rhythmic hissing at a certain pitch, and it affected my inner ear. Then he finished it off with a volley of hacking techniques that wore me out and reduced me to an incoherent state and I went to the hospital for five days.

It was an impressive hack, with a rising arc, a climax, and a skillful denouement, almost as if he were laying me out for the night or beyond--in a long box, perhaps.

Greg seems to save the hissing for when he's really angry, such as when I introduced new email addresses to my shoutout page the other day.

He uses this psyops method because it does physical and psychological damage. I've captured the sound on a video recording and posted it in another entry here, but it's hard to experience it through the recording. After all, computers do hiss sometimes. It's normal.

But when my computer awakens to sustained and rhythmic hissing, at times when Greg would be especially angry--like when I was writing a book about him--I witness a meaningful pattern. It's not a normal computer sound. Also, this psyops seems of a piece with his other death-dealing hacks presented here. He's surely one of the evil characters who hunts the skies in the dark webs.

June 26, 2025. Back in 2017, I felt like my "Polemical Literature" essay was a little off when I read it after it was published in the Observer. It seemed to contain items that I had not put in. At the time, I didn't suspect Greg, though he had deleted or changed parts of my novel and short story manuscripts. My editor wouldn't have changed anything without telling me first. I had a sense of mysterious uncertainty about the changes, but I moved on from it.

I wrote that people could Google me and find the post on my site, and I had a lot of visits. For a while I continued to post on the Iowa Facebook page and received just as many likes.

But soon my posts on that Facebook page were limited to one or two likes. Then my posts were restricted. I could post but never received likes. Greg can actually limit the number of likes a post gets. He can also cover a post so that it's not visible to anyone. This is part of Greg's gaslighting. He wants me to think that no one is interested.

He has done this on my own Facebook page. He seems to preset the number of likes a post will get. At one point, for about a year, I was getting five likes for every post, and all the likes were from other countries, as if he wanted to avoid Americans hearing word about his behavior.

It seems precious to bemoan your Facebook likes--until you realize that it's your censor who is limiting your voice.

Recently the "infected" post on the Iowa page was deleted. I doubt admin would hunt down that post from so many years ago and delete it. Greg deleted it.

Here is a representative Iowa Facebook post before the censorship began.

He has published almost no women at Slant, and the swapping of my photos with women suggests he believes women are inferior. It's a way of laughing at me, as if to say, "Ha ha, I've replaced you with silly little girls, because that's all you're worth"--something like that. One of my screenshots showed two swapped women's photos next to each other, but he has deleted that.

This has been going on for months.

In 2013, I received the flattering offer to teach Advanced Fiction at an Idaho university after my first book, Down in the River, appeared. My boss was a great writer I'd read before, and I made two friends in the department. I'd taught creative writing elsewhere, but now I was teaching seniors. It seemed like a positive jump.

Half of my students were enthusiastic about my class. But it was a religious-influenced public college and parents, especially the mothers, were heavily involved on campus.

The other half of my class disliked the (non-explicit) sexual content of two of the stories I presented on Blackboard--by Alice Munro and Chris Offutt. Two of them took up the curious activity of yelling in class, not at me, but just yelling their discontent.

Some also suffered in my intense workshops for this advanced class. My model was the Iowa Writers Workshop--extremely frank in terms of craft. I had received difficult workshops as a grad student, and felt they were some of the best experiences I'd had as a writer. Nothing was handed to you in a care package. You were able to see what worked--especially what didn't work, and why. That said, after this advanced workshop, I moved on to other teaching roles and discovered the value of kind workshops, though occasionally I still find the stray serious student who prefers the Iowa method.

When half the class didn't like my teaching style, I assumed a defensive posture of snobbery, holding to literary standards and ripping stories that were overtly religious or gratuitously conventional.

Nervous before the unhappy students, I gave grumpy workshops, not personal, but frankly negative regarding craft. I had a habit of shutting my eyes too long when I talked: weird.

In addition, in the red state of Idaho, it was hard to find a med-check doctor for the lithium I needed. I soured in my intermittent treatment. One doctor believed I was a "drug seeker" when I landed in the emergency room for medication.

During class I made light of my emergency room visit and revealed my diagnosis--a confession that was welcome in a Portland creative writing classroom at that time, but not here. Boise was a gorgeous city with many writers, but its pockets of social conservatism were deep, even among Democrats. I was unaffiliated, an inscrutable type in the margins of the culture wars. In addition, this was also the start of what became a ten-year hacking campaign that a Christian leader and former associate had commenced after I refused to do what he wanted me to--the subject, in part, of "The Lord's Hacker"--and I hadn't yet made a psychological adjustment to living with a hacker.

Soon a mother or two waited outside my classroom to meet their children--college seniors--after each class. I met with a dean about a student whose constant yelling disrupted the class. He believed it was better for the student to leave the class and finish the coursework one-on-one with a different adjunct. Then a professor called me. He said he wasn't going to have some adjunct kick out a student he had worked with, but the student remained outside of the class.

A second dean at the Idaho university emailed me and wanted to bring several members of the Care Team to observe my class, and I, foolishly, swore at him on email and referred to some of the students as "drama brats," and he fired me.

In the end, the student newspaper published an article explaining that I was fired “with a life-time ban." The author, a student of mine who was the managing editor at the student newspaper, noted good things about my teaching and interviewed students who liked me, but that lifetime ban, in the first line, was a hit job--a fabrication that seemed two-thirds mental health freakout and one-third sexual prurience in this conservative environment. He also used the same photo that Boise Weekly used for my interview "Enter the Mausoleum," concerning my novel about a grave robbery--the photo is a bit stern.

The chair was quoted in the newspaper stating they couldn't discuss my firing for legal reasons, but the dean had already placed my termination letter on his university site, as if they wanted to suggest to the public that it was bad, to justify my firing, while communicating to students and parents to rest easy, that nothing serious had happened.

A year later, the new student manager at the newspaper, Patty Bowen, retracted the "lifetime ban" language and stated in an email, and on the site, that there was no such ban. There remains an aggregated copy of the original article. It seemed to disappear from the internet six years ago, but recently it has returned as if plucked from oblivion and placed in my high Google pages.

At any rate, I was pleased to find Patty, a journalist who was willing to locate the facts. Before getting back to me, she wanted to look into it and make sure that nothing shocking had happened when I taught there. She works at Meridian Press now.

Greg cares a lot about the concept of a job. He lost his job at Image and feels ashamed about that. But he also lists "artist" or "writer" as his job on LinkedIn, so there must be a crosscurrent of desires running through him. "Academic writer" would be the best description for his avocation. I'm actually an artist and a writer, but he ridicules the part-time jobs I do so that I can write.

Greg's Always Hunting and Hacking

April 13, 2025. I’m staying at my ex's and Greg is hacking her computer. If this video is allowed to go through, you can hear her computer hiss. When Greg realizes I’m videoing it, the hissing dies down. Turn up the volume all the way before you watch it.

.jpg)

Background: Judge Charles Carlson

Highlights

Enemy Email

Illegal Porn

My Hacker Fired for Sexual Harassment

My Hacker is Known for his Dick Pics

Ashley Madison and "The Evil Dead"

These screen shots were deleted from my phone. It's lucky that I had posted them in a private Facebook post.

Manipulates Dating Site

In May 2019 I dated a black woman through a website in Cincinnati when I was divorced. She was a Christian and wanted me to be one, and it didn't work out. In a few weeks, I looked at the dating site again and saw it was all very large black women who were looking only for sex, at least that was all I could see on the site. He seemed to say, Oh you want a black girl? Try one of these.

Sends Infected emails to My Student

Hacks Colleagues and Editors

Spoofs Dick Pics to my Date

Another Editor Hacked

Psyops Noises Issue from My Computer

Hospital Stay

Swaps Digital Info on Caller ID

In November 2023 my hacker switched the name of my doctor and my pest control in my phone's address book, to suggest that I needed to be treated like a pest. He often switches caller ID so I don't know who is calling. My digital world is so full of glitches, I don't believe in glitches anymore.Friend Requests From Kids

Blocks My Phone Calls etc.

Sometimes I can call my doctor's office, but it rings and rings. Or a robot answers and puts me in a cue, but it's not the standard music that my doctor's office plays, and no one ever picks up.

Spoofs My Landlord and Tries to Get Me Kicked out of My House

At the very least, my hacker is certainly not being careful right now. His brand has tanked, and he blames me instead of his behaviors. He's doing things, with greater repetition, that he wouldn't have done last year.

It was Wolfe, pretending to be my son! Yes, things are getting weird. No surprise, he deleted this digital touch exchange, and deleted the screenshot of it later.

Suicide Included in My “Friends”

Constant Social Media Censorship

In November 2023 I joined the Facebook page Beat Poems On the Road and was receiving 500 to 900 likes on my posts. The admin, Steff, got hacked and cut me off. In Facebook pages I frequent, my hacker often uses an avatar to bark at me and complain to the admin about me. If this doesn't work, he hacks them until they drop me. I have experienced this five or six times. In the case of Beat Poems, I believe he couldn't handle that I was getting so much exposure, and he had to put an end to it.

One judge, in 2021, told me, when I mentioned my hacker's porn harassment online, "That's his free speech!"

There is something wrong with our laws on cyber harassment right now. We can't seem to locate a sensible position on the issue. When we police speech online, we tend to target political speech, so we correct that overreach by backing off and allowing ghastly crimes to go unchecked.

If someone sends you death images and porn and then twenty pictures of your son or daughter from your iphone memories, in meaningful and threatening repetition, not even the fiercest Libertarian would say, "Free speech! I love this!"

But I was pleased to hear this judge agreed that his behavior may well be psychotic and dangerous and that the internet is a running ground for criminals. At least she didn't pretend that all is well and that it's free speech.

"Change your passwords." This is advice I've heard from tech people, many who make a lot of money. This advice is also a favorite of cops. Even IT "experts" will tell you that you need to change passwords often. You should change them to guard against low-level types. But advanced hackers use a technique called "forced entry" to bypass passwords. I remember when I was in Pittsburgh I was changing my passwords all the time, and that never worked. Greg may have some program that captures password changes. But don't forget, Russian and Chinese hackers have recently blasted their way into Pentagon computers, despite the most advanced defenses in the world, and owned them at every level. A really good hacker can certainly get into my computer and yours.

At any rate, yes, he gets into Gmail, Facebook, Blogger, LinkedIn--all of the apps.

Regarding his ability to reorder Google content, one person told me years ago, "I doubt he has access." Again, hackers hack. They don't ask for passwords or dig them out of your trash. I have documented that many items rise and fall rapidly on my Google pages. Greg even wallpapered my Google pages with porn descriptions--In 2019 I Googled my name and there they were (see below)--and it took three days for the junk to clear out.

There's a lot of innocence about hacking. But things are changing. More people know what spoofing is now, for instance. The FBI knows that a spoofer owns your phone and can send your pictures of your naked body to your husband's friend, so it looks like you're sending it to flirt. And the FBI no longer says corny, low-level stuff like, "Did you change your passwords?"

If an IT dude who seems smart about defending your computer but has no experience dealing with an advanced hacker--if he tells you "nobody's getting in" and "change your passwords," I hope you'll be a bit skeptical. Be skeptical of me too, but at least I have had some experience with a master hacker, and I've shown fifty-plus pages of real-life hacks. It's true some of it is just based on my word. But most of it is based on alarming screenshots and narrative of my experience.

I don't wish to dismiss all IT people, only to say that most of them aren't ready to defend the Pentagon. But one IT guy I met actually had a lot of experience with hackers. He worked with a lawyer I employed last year. He was familiar with top-drawer hacking. When he looked at my GW post, he said it was obvious that I'm the victim of a crime. The lawyer said the same thing, but they asked for money I didn't have beyond the $700 I had already handed out.

Places Face on My Blog as Warning

March 20, 2024. Greg placed his face on my blog after I posted "A Christian Leader's Life." My blog has always used the picture on the top post for the site picture (after two or three days), no matter how popular a post below it might be. This Moses pic was on my blog for two weeks.

Deleted Blog Followers

Eugene Weekly

March 27, 2024. After I posted "A Christian Leader's Life," the Eugene Weekly editor said she wanted to do an investigative article on Wolfe. When I called days later, I found a generic, robot voicemail and left a brief message. Later in the day it struck me as odd that the voicemail would be generic. He has placed fake voice systems on my phone before.

I left my house, getting away from Wi-Fi, and called again, down the block. This time there was a real voice thanking the caller for contacting Eugene Weekly, but it was closed so I left no message.

Greg has intercepted many of my calls, often just to be a creep, but sometimes to keep me from talking to someone he doesn't want me to talk to.

Eugene Weekly

Questions

I wanted to address any who might believe I have no evidence, simply because I lack an IP or a photograph of my hacker caught in the act. As Judge Charles Carlson told me at the hearing, I have evidence that would be persuasive in civil court, and my assertions raise many questions that point directly to Gregory Wolfe.

For instance, who placed Greg's picture on my blog for two weeks, a threatening gesture, after my post went live? Only my hacker would place his image on my blog.

Who removed the many followers of this blog before I posted "A Christian Leader's Life"? Some other nemesis?

Who deleted the emails from my hacker to me and then restored some of them but not all? Who else had a motive?

Who deleted my email containing the porn descriptions that my hacker used to cover my Google pages, the email I had sent to the scholars? Who else would want to?

Who edited "A Christian Leader's Life" a few times after it went live, to convey a frivolous and unedited and sometimes confusing vibe so that I had to keeping rewriting it?

Who replaced the screenshot of the fake email that contained the iPhone memory?

Who deleted the photo I took of my son sitting in front of his computer? It was wallpapered with my book cover art that my hacker had helped create. My hacker had the motive.

Who is so focused on my son that he has to keep sending me his pictures to convey a threat? Who else deletes his texts? Some other random hacker?

Who demeaned, repeatedly, working class people in fake blogs and on my blog, just as he demeaned the working class background of one of the women who fired him?

Who else would spoof my police report about my hacker, placing my landlord’s name and email and phone on the report?

What else would be interested in my communication about my hacker to the police?

If it was a different hacker, he must have been very sympathetic to Gregory Wolfe and spent a lot of time covering for him and concealing his crimes.

Froze My Site Visit Counter

June 22, 2024. Right after I posted this today, I saw thirty people visited the site right away. Then the counter was turned off. That's Greg's way of staying in charge--again with the censorship. He also turned off my visit counter when I posted the two paragraphs from Poets & Writers last week. He doesn't believe anyone should get notice that's a little better than what he has. He's also angry about that post because he doesn't want to explain why I dumped Slant, especially since he pretended that it was his idea that I left--awkward! [The counter resumed six hours after this post went live].

When I blocked one young prostitute, my screen froze on my phone, but I was able to block the rest on my computer.

June 28, 2024. Greg deleted this polar bear photo from this site and from my desktop today, and I took another screenshot of it. He has deleted other photos related to his harassment concerning my son, as described elsewhere in this document, possibly because he doesn't think that obsessing about someone else's child is a very good look. He would be right.

Some radicals say that Christians are often perverts. It’s more accurate to say that perverts are often Christians. They need an identity behind which to hide. Most perverts understand they can’t live in society as the way they are. Some become Christian leaders. Christian author M. Scott Peck explores this phenomenon in People of the Lie.

This morning when I opened my phone I found that an off-white “card” had been placed over most of the text of our emails. Last year, Gregory Wolfe sometimes placed such cards on the very Word doc of The Lord's Hacker as I was writing it. He never left it there for more than a minute. He was just using one of his myriad hacking tricks and wanted to send the message that he’s in charge.

This time I believe Greg's covering up my emails with the editor communicates that he’s going to cancel my arrangement with the editor, that he’ll ruin it somehow, as he always does.

Greg’s censorship is tricky in several ways. Not only has Greg sent infected emails to publishers in my name—and will likely do so again—but there’s also the psychology of the publisher to consider. Though most publishers find censorship despicable, they also don’t want to walk into controversy or open themselves up to attack by malevolent actors.

It’s easy to look back at beloved writers who were censored and wonder why they were so alone in their fight, like Isaac Babel and Rousseau.

It’s only later, usually after the censored author and his enemies are dead, that supporters seek to publish their censored work. I don’t place myself in that company of luminaries—nor do I see most rejections as censorship—but I do expect fearful silence and cold shoulders from any publisher who learns of the hacking. That’s what Gregory Wolfe wants too. He loves to see his terror result in destroyed relationships and neglected books. He’d burn them if he could. Being a publisher must offer psychological cover for this passion he has for censorship.

All Greg has left is the ability to frighten people. When Orwell imagined the future as a boot stomping on a human face, he surely conjured tyrants like Gregory Wolfe. I hope there are some, like the fighters in the French Resistance, who are willing to take some risks against a true enemy of humankind.

They do everything by the manual. The FBI even has a specific technique of taking phone calls. They pepper the caller with snarky questions and comments. "What's this guy's motivation?" or "I can guarantee he doesn't have any interest in your Facebook page." Then he or she begins the rapid closure of the phone call, talking in the dazzling speed of an auctioneer: "Thank you for calling the FBI. This call will be documented and you are free to follow up with a complaint." And they hang up on you. All intake people do this exactly the same way.

I know they are looking for words like "I'm going to kill you," etc. and that they are trained to dismiss anything about social media or otherwise frivolous concerns. But my hacker, in fact, uses social media and my Google page as a template in which to present child death images, underage porn, a photo of my friend who committed suicide, etc. It's true the FBI is looking for extortion and bodily harm, but my harassment case is horrifying and dangerous, not frivolous, not imagined, not paranoid, and deserves an investigation.

Judges also tend to dismiss almost all hacking claims. I've stood before a few judges who were visibly angry that I even brought a hacking case. Even while newspapers and attorneys say that Russian-style hacking is increasingly common in America, judges and law enforcement respond to this reality by refusing to believe it even exists.

Since this response makes no logical sense, I believe this shutting of the eyes is a psychological reaction. After all, law enforcement has not kept apace with the high-tech criminal hackers. To open up law dockets to hacking cases would be like opening a portal to a howling infinite that would cause headaches for courts, judges, and law enforcement.

And this is why judges and law enforcement regard with anger and distaste the person who brings forward a hacking case. They can't do anything about it! They don't have the tech. Psychologically they have hardened themselves against you, knowing that your possibly reasonable case can't even be considered. You almost become a criminal in their eyes.

As far as the FBI, I believe the only luck I'd have there would be to find an individual agent who thinks outside of the organization. I've been lucky to meet one police officer, one lawyer, and one judge who are indeed able to think independently about this issue, and now I hope to meet one FBI agent. I'm not holding my breath, though.

By the time I knew her, she had mostly normalized. She had taken one of my creative writing classes and we started dating later. When my then-wife Daphne asked her to stop sleeping with me, she wrote that she liked me too much to stop. I was glad, since I was in love with Jane. After all, she and I had both been cheated on. We didn't need to honor those commitments. But we struggled with the affair. One day I was never supposed to contact her again. The next night we'd fly to each other in some city park. Even years later, we weren't supposed to contact each other, but we still made plans to catch up.

In 2013, when I was remarried, Jane wrote that she hoped "we'd always find a way to love each other in some way." My new wife, Becca, was uncomfortable with this contact, and I stayed out of touch with her for a couple of years, until Becca was okay with my catching up with Jane on occasion. There was nothing romantic about my and Jane's contact at this point.

In 2015, Jane told me on the phone that I was "not allowed" to write about anything she'd told me about her husband and the woman he'd had an affair with. She said it was her material. I'd told her I was including some of that story. We kept in loose contact. We were trying to stay out of touch, but we'd exchanged emails and planned telephone calls over the next three years. She was on my email shoutout lists for my first book, and in 2018 she said that was too much. Once again, we decided to stay away, but ended up planning telephone calls.

Her mother told me she was "our little drama queen." She was all over the map in terms of how she perceived a situation, then insisted that she'd had one fixed idea all along.

In 2019 I got divorced. A few months later, in an abject mood, I wrote Jane that I'd always love her, remembering the note she had written me. She showed my email to the CEO of Wipf & Stock, her new boss and my publisher.

It had been foolish to write the email I did, so many years after the note she'd written me about finding a way to love each other. Then she went to work for Gregory Wolfe, after he was fired for sexual harassment--my first publisher and active hacker.

I was surprised she went to work for Gregory Wolfe. Neither she nor I were Puritans. After we had broken up years earlier, we both went through months of haphazard hookups with multiple people, like those recovering from a breakup often do. We were sloppy, stupid, but not cruel.

But I had told her about Wolfe's hacking and sexual harassment, and I supposed she didn't care. Greg's gaslighting of a young intern was a calculated moment of dishonesty and cruelty. It wasn't a sad dalliance that might be forgiven.

In 2022, after I mentioned the woman who influenced Karmina, without naming Jane, on a public Facebook post, I received a rare manic hacking that went on for days. I doubted that Greg would take it on himself to hack me for a Facebook post that didn't name Jane, so I believed that she had complained about it to her former boss, Gregory Wolfe.

I often give updates about characters I'm writing and mention the people who inspired them. Many times I have posted about my first wife, Daphne, who had told Jane to stop sleeping with me. Daphne is a smart Latina poet who attended Reed College. I have also written about Becca, who is all over The Lord's Hacker--she's the exemplar of that book--and who remains a good friend. I have posted about many old girlfriends, wives, friends, and family members, in public and private posts, and none of them scandalous. And Jane's character in Karmina is compelling and sympathetic.

In 2023, I posted a photo of Jane's laptop resting on a cafe table, while referencing Karmina and not naming Jane--the picture was taken in a cafe in summer, and evoked the mood of the book--and again came the savage hacking in the style of Gregory Wolfe.

I have written about many people in magazines as well, with changed names. No one but Jane and Greg has ever implied that I don't have the right to write about my own experience.

On June 21, 2024, a few days after I made public a positive rejection of Karmina, I received a similar brutal hacking--in excess of the usual hacking--and again I believed Jane had told Greg that it wasn't my material to use, and he hacked me like a devil. Why would Greg care if Karmina got rejected somewhere? She must have complained to him again.

Jane has a history of calling strong men as needed, such as when she needed a washing machine and tearfully called her dad. Then she outed him later, by name, as a Trump supporter in an online magazine, as if forgetting her own questionable right-wing past [the article is now offline]. I'm not a Trump supporter, but goodness, leave your dad alone. And I know Greg likes to play the strong, chivalrous Christian leader when he gets a chance, and I bet he likes flexing his hacking muscles for her.

I had emailed Jane about Greg's shocking activities as a hacker--he lives in the very toilet of the world--but she wasn't interested. She commenced her own hacking efforts, though still a Christian. In 2023 I saw she'd covered up one of her letters online that she wrote in support of the man who kidnapped his kids at gunpoint. When I clicked on it, a message read, "your computer is now infected."

I believe I have been hacked about ten times by someone who uses this style of hacking--"your computer is now infected"--and it seems connected to the person who tried to cover up the letter Jane wrote. That would suggest Jane was the hacker.

In 2024, when I clicked on her letter in support of the Christines, it went to a line up of porn pics--a change in tactics. She was using porn now, like Gregory Wolfe, both of them Christians. This seemed to me like Jane's new method of blocking the letter she'd written when she was a member of the cult. I was able to take a screenshot of the letter before it bounced to porn.

I received more "Your computer is infected" hacks. I assumed Jane was communicating that I needed to avoid writing about her.

Only one passage in Karmina explores what I heard regarding Jane's husband and his affair. Fictionalized, it involves a birth and burial scene in a park in Ashland, and since I heard the story and made it fiction, I intend to use it. I already have.

If Jane is working with Greg to censor my book--and sharpening her own hacking tools--she is breaking the law, following her mentor into a dark webs criminal underworld. She might retaliate against me for exposing her, but that's what hackers do. They want to live anonymously in their crimes, and they shriek when the sunlight reveals their behaviors.

When I knew Jane, she was an uncommonly bright, religious church woman with many contradictions. She danced tango, discoursed on the books she read, disciplined her kids with heavy wooden spoons, and made friends with men who could help her financially or otherwise. She was also a warm, inspiring, and impressive person.

However, now and then Jane appears to be drawn to men who are extreme and potentially dangerous, as if such men can step in and provide comfort and assistance on a bad day. She invents narratives about their goodness while she impugns their adversaries, just as she did when she posted about her armed Christian patriot friend, Brian Christine, years ago.

Hi everyone!

I wanted to write you really quick and tell you about a family we

know that is in dire need of help, and especially PRAYER! Their names are Brian and Ruth Christine, they have five girls Bethany, Miriam, Lydia, Olivia and Abbey Rose.

Some of you who are from Oregon may have heard of this family as their case has received quite a lot of media coverage. For those of you receiving this who are unfamiliar with the Christine family, I will try to give you a brief account of their situation.

Brian and Ruth are a young married couple who, after meeting and

marrying in Ruth's native England, moved to Indiana where Brian was born.

As they began to have a family their desire for their children was to give them a Christian based homeschooled education. Brian had a lifelong dream of converting a bus and traveling around the United States, so the couple set to work customizing a home on wheels with all amenities. Their intention was to incorporate their travels into the children's education while they were still young, giving them a hands on experience. For example, while studying rock formations, visit Carlsbad Caverns... you get the idea. Brian had an internet based business which allowed him to work while they traveled the

country for about a year, very happily, when they arrived in Grants Pass, Oregon. They made friends, got involved with the community and thought that they had found a place where they might want to stay for good when their traveling adventure was over.

Then the unthinkable happened.

The Christines had been participating in a program at the public

library with their oldest daughter Bethany, then 5 years old, whom they had taught to read. They had occasionally parked their bus at the library while the children took part in library programs and Brian did computer work. Someone observed their bus parked behind the library, and for reasons unknown, made an anonymous call to child protective services say that their were some kids living in a bus behind the library who looked hungry.

Ironically, when the police showed up the children were in the bus

sitting at the table eating sandwiches for lunch. Their mother was taken aback when the armed policemen and child services workers indicated that they were seeking the children. Surely this must be a mix up and they were looking for someone else! Ruth promptly sought Brian, who was working in the library. By the time the family returned to their bus it was surrounded by police cars. When they refused to let the children go with social workers, Brian was arrested and the three oldest girls Bethany, Miriam and Lydia were whisked to the hospital for physical evaluations. Ruth, who was at the time pregnant with their fourth child, followed the children to the hospital,

distraught and wondering what to do.

At the hospital the three oldest girls were subject to interviews

filled with leading questions which manipulated the toddlers into answering in a way that would make the parents guilty of abuse. they were also given thorough physical examinations which diagnosed one of the girls who had a Band-Aid on her forehead as having a minor skull fracture, although no x-rays were presented to prove this when the parents requested them. The children also had to go through invasive sexual examinations although there were absolutely no allegations of sexual abuse. They were then placed in

foster care.

Brian and Ruth were told that they would be given visitation with the

possibility of having their children restored to them, only after they went through evaluations and the proper rehabilitation programs. They were obviously furious and refused. Over the course of the next several months they went on radio shows, picketed the court house and fought in court to get their children back. During this time Ruth gave birth to Olivia, their fourth daughter, and placed her in the care of Brian's mother in Indiana.

The state of Oregon sought relentlessly to obtain custody of Olivia as

well. It seemed that the more Brian and Ruth drew attention to the abuse of power exercised by Child Protective Services and the harder they fought, the more the state sought to demonize their character to the media. Being of limited financial resources and seeing no end in sight, Brian and Ruth finally decided to play the State's game to get their kids back. But the couple were then told that it was too late and their children were to be adopted out soon. Brian and Ruth were however awarded visitation with their children.

With their backs up against a wall, they did what most parents would

do, they took their kids back. After a visitation, Brian followed the social workers van and allegedly at gunpoint ordered the workers out of the vehicle. They got as far as Montana with their children. They were then captured and Brian and Ruth were sent to jail. Some months later, Ruth gave birth to their youngest daughter, Abbey Rose while shackled to a hospital bed.

You may be asking yourself, why would the State go this far if they

were innocent?? It's not a pretty answer. Child Protective Services in the state of Oregon is an agency with little or no checks or balances. For every child in foster care and every family going through "rehabilitation," they receive large amounts of funding. The system is clotted with cases that are not authentic abuse or neglect, for instance, cases where a parent spanked a child in a public place, or if someone deemed a child the child looked dirty. (Anyone with children who play outside knows how easily children get

dirty!)

Recently, federal policies have been put place to provide the state

with thousands of dollars for every child that is adopted out from their system. It has become a lucrative business, with no accountability. Basically it's all about money, and rules that are not

right. Many of you receiving this email who are from Oregon have seen first hand the corruption in our state.

So what can we do? A LOT! Currently Ruth Christine is out on bail

trying to prepare for their trial which will be in Roseburg, Oregon

beginning April 30. Pray for the jury selection. Pray for the trial. Pray

also for their children. After a heated court case and lots of negative

publicity for Oregon CPS, the three oldest children were adopted out to Ruth's parents in England and the two youngest girls are under guardianship with Brian's mother.

Forward this email to others.

Donations. Ruth is trying to raise money to provide for legal

assistance and Brian's bail. If Brian were out on bail it would enable him to have more contact with an attorney and better prepare for their trial. Also if Brian and Ruth are sentenced to terms in prison this time would be invaluable to them to be together before being separated. Brian's bail is set at $60,000, currently $11,500 has been raised. Donations can be sent to:

. . .

Watch Ruth tomorrow April 18th on NBC's The Today Show at 7:30 am and find out more about them. Since Ruth has been out on bail I've had the privilege of spending a week with her. I can't tell you how much it has blessed my life and my children's life. I continued to be amazed at how in the midst of so much she has a way of ministering to others and glorifying God even in her trials. I believe Brian and Ruth to be sincere and innocent individuals, and I hope that you will join me in doing what we can for this family in need . . .

God's blessings on you and yours,

.png)

.png)